Sequential Logic

8. Sequential Logic

An important characteristic of combinational circuits is

their inherent

finiteness: every combinational

circuit

- is composed of finitely many gates;

- has finitely many inputs and outputs;

- has finitely many input-output paths;

- performs finitely many basic logical operations

to compute its output;

- takes a finite amount of time -- bounded by its $t_{PD}$

specification -- to perform its computation;

and

- has a finite functional specification (in the form of

a truth table or finite Boolean expression).

While the finiteness of combinational circuits has some

advantages, it limits the set of computations they can

perform. We can design, for example, a combinational device

capable of adding two 32-bit binary numbers and generating

a 32-bit result, a useful building block that will be explored

in subsequent chapters.

Suppose, however, we need to add a column of N 32-bit numbers

for some N greater than two.

We could design a combinational adder having N 32-bit inputs,

a task that becomes tedious for large N; but such a device

would be incapable of adding N+1 numbers when the need arises.

The fixed, finite hardware resources of any combinational device

we build will limit the set of computations it can perform by bounding

the number of inputs accepted and the number of logical operations

performed in the computation.

To deal with a broader set of computations not amenable to

such bounds, such as the addition of N numbers for arbitrary

finite N, we need a way to somehow relax these bounds.

A resourceful accountant faced with this problem would

recognise that adding a column of N numbers can be decomposed

into a

sequence of 2-input additions, each adding a new

input to an accumulating sum.

In effect, the finiteness constraint of his combinational

tool is circumvented by expansion in another dimension:

time.

In this chapter, we explore the liberation of our digital circuits

from the finiteness bounds of combinational logic by technology

and engineering disciplines that allow circuits to perform

sequences of consecutive operations.

The resulting expanded class of digital circuits are historically

called

sequential circuits, meaning that they respond

to time-ordered sequences of input data rather than producing outputs

that reflect only current inputs.

System State

8.1. System State

Our repertoire of combinational devices is clearly missing a

critical function if it is to perform useful sequences of

operations:

memory of some piece of information

that persists from one step of the sequence to the next.

There needs to be an evolving record of

system state,

capable of changing from one step of the sequence to the next

and of affecting the computation at each step; without such

state information, the second and subsequent steps of the

sequence would duplicate the first, without any cumulative

benefit.

The accountant using a 2-input adder to add N numbers must

provide this memory of system state -- the accumulating sum -- by means external to

his combinational adder; if we are to mechanize his approach

in a sequential circuit, we need a device capable of performing

an analogous memory function.

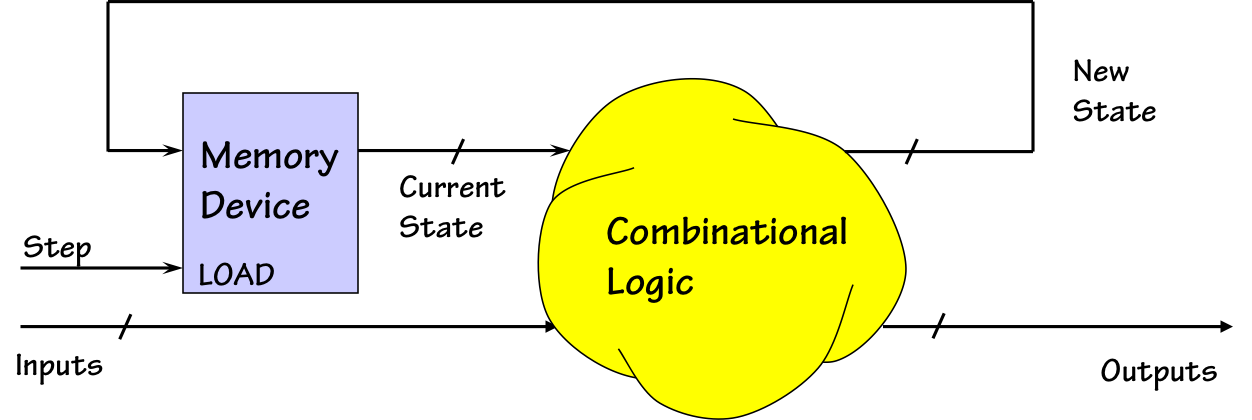

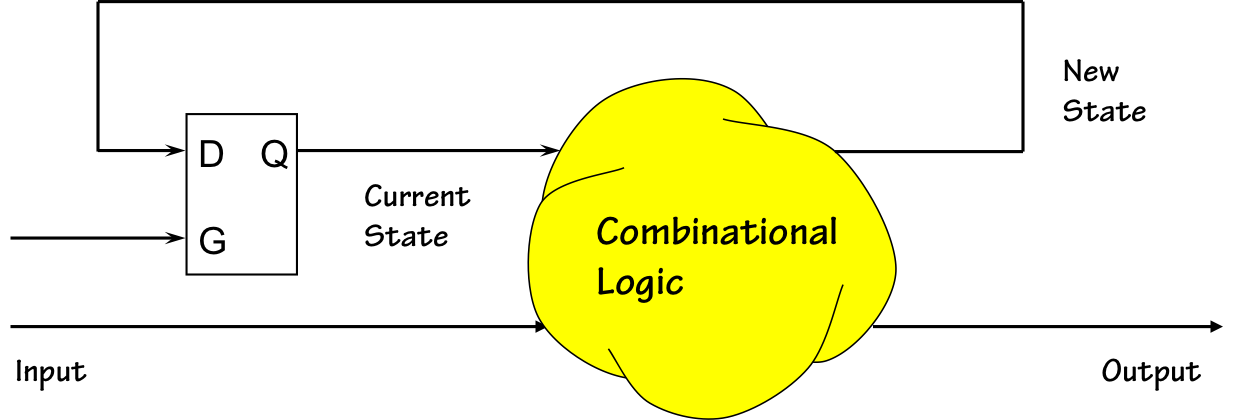

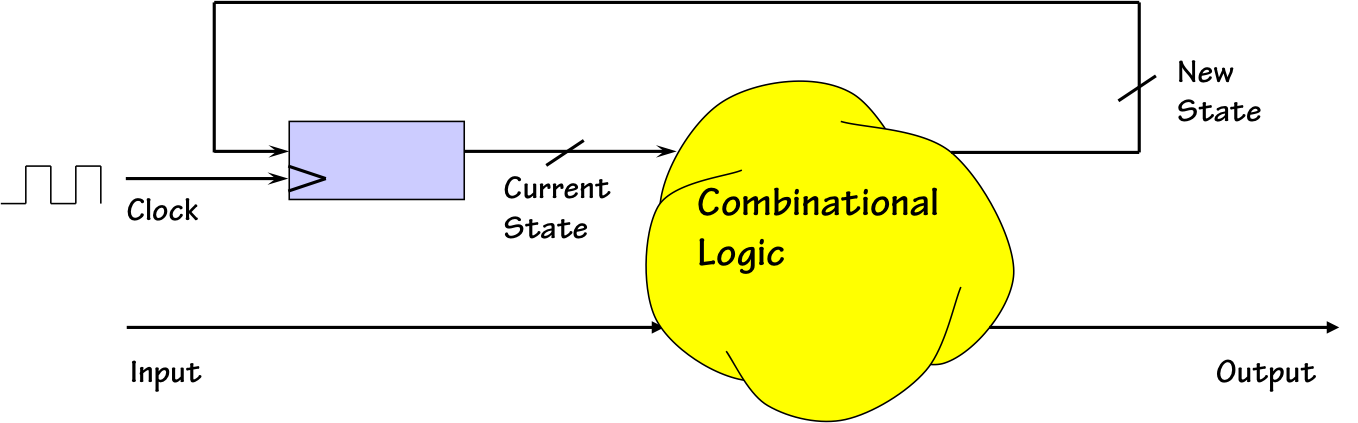

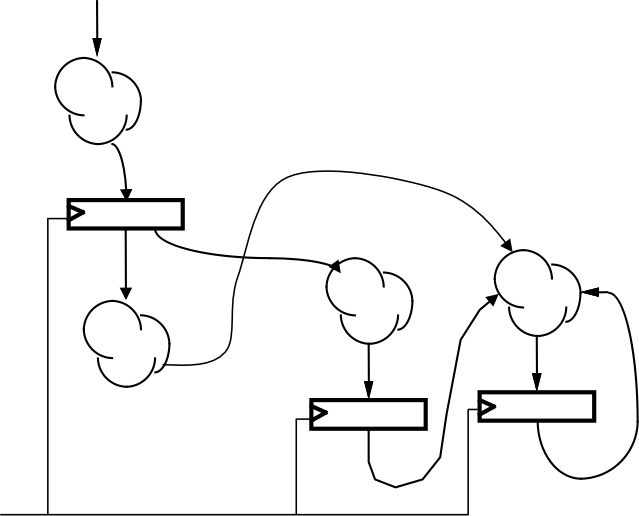

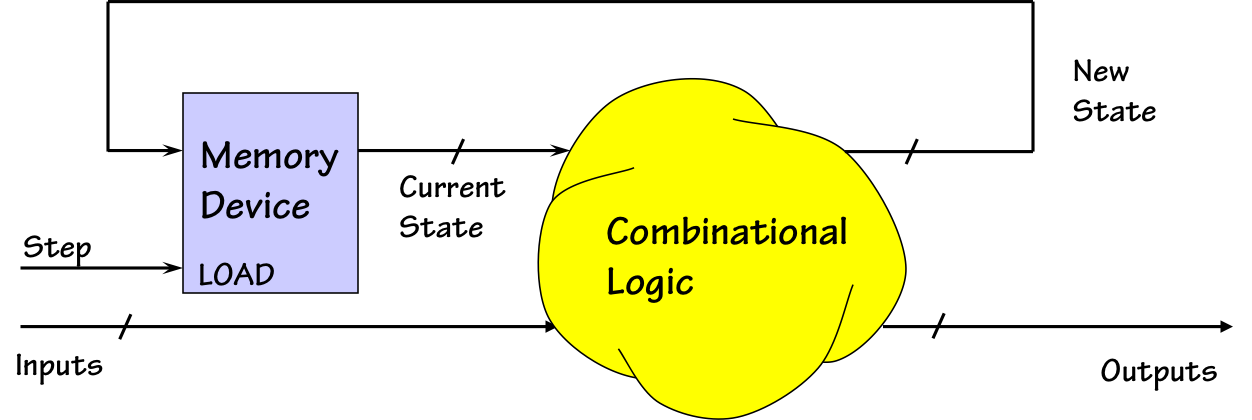

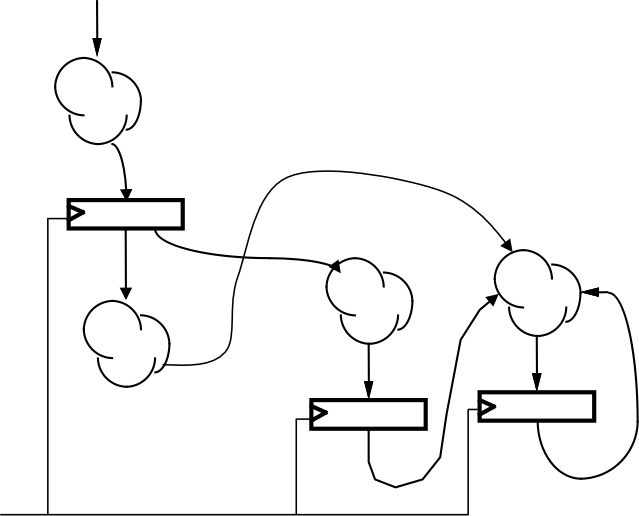

Sequential Circuit

Sequential Circuit

One model of sequential circuits is shown to the right.

It includes a digital

memory device capable of

storing some finite number of bits representing the system's

current state, as well as a block of combinational logic

whose function is to compute both system outputs and a new state

from the current state and system inputs.

In addition to other binary inputs and outputs, the sequential circuit

has a

Step input by which it can be instructed to move from

one step in its sequence of operations to the next. When

Step

is signaled, the memory is loaded with the new state information at its

inputs, discarding the previously stored state. Conceptually, the

system moves from the state encoded in the previously stored bits to a

new state encoded by the bits just loaded into memory.

An important functional distinction between this model and pure

combinational logic is that the outputs produced at each step

of the sequential circuit's computation may reflect the current

system state as well as the current inputs. The current state

will typically reflect some aspect of the system's history, e.g.

the accumulated sum of previously entered addends.

Storage Devices

8.2. Storage Devices

A technology that is missing from our combinational logic toolkit

is the memory device needed to communicate state information between

steps of our sequence.

Many different technologies can be used to effect the storage of

digital information, including electromechanical, chemical, audio,

and optical approaches; the history of digital systems is rich

in interesting and often clever memory designs. Some memory

technologies are

volatile, holding information for

brief periods (so long as power is supplied); others, like

magnetic memories or punched cards provide nonvolatile storage.

We present a brief glimpse of two widespread memory technologies in

Section 8.4: a volatile approach used for computer

main memories using charged capacitors to hold individual bits,

as well as nonvolatile magnetic memory used in disk systems for

files and other longer-term storage needs.

However, the memory technology primarily used for small, short

term information like the state of a sequential circuit is

typically constructed directly from combinational gates, using

carefully-constructed feedback loops to effect a bistable (2-state)

digital device.

The introduction of cycles (and hence feedback) in circuits of

combinational components seems deceptively simple, but requires

tedious attention to engineering detail to design provably reliable

storage devices.

In

Section 8.2.1 we endure this tedium once to build a

single-bit storage device, the

flip flop, and use this

as our basic building block for the storage needs of our sequential

circuits.

Bistable Circuits

8.2.1. Bistable Circuits

In this section, we will explore the "bootstrapped" construction

of memory devices from combinational logic. The key insight

behind this construction is that, by introducing cycles in a

circuit containing combinational logic, it is easy to create

circuits that have multiple stable states in the logic domain.

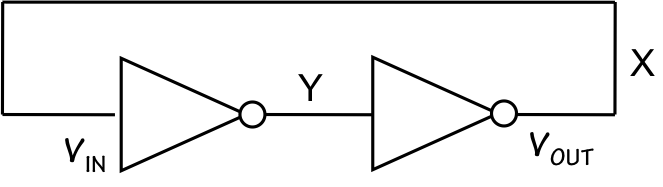

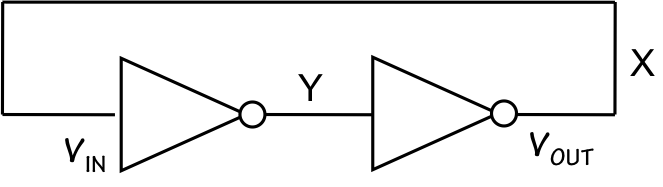

Bistable Circuit

Bistable Circuit

Consider, for example, the simple two-inverter loop shown to the right.

Given our understanding of the behavior of inverters in the logic domain,

It is easy to convince oneself that this circuit exhibits two stable

states -- with the node marked $X$ representing a valid $0$ or $1$,

respectively, and the other node $Y$ representing the opposite value.

In fact, this intuition reflects the only two solutions to constraints

on these logic values imposed by the specifications of the inverters:

namely, that $X = \bar Y$ and $Y = \bar X$.

Which of the two states the circuit is in can be used to store a

single bit of information, suggesting an easy path for the creation

of simple memory devices using combinational logic.

While this approach can be made to work, the simple logic-domain

analysis above seriously understates the engineering complexities

involved.

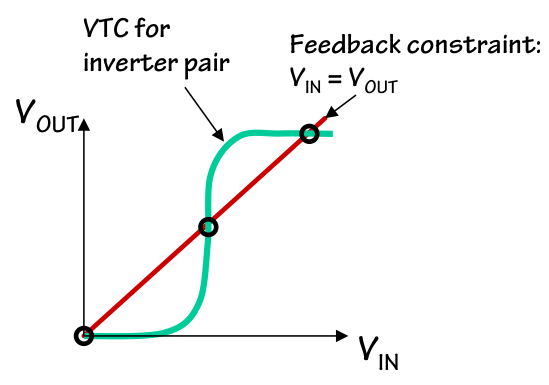

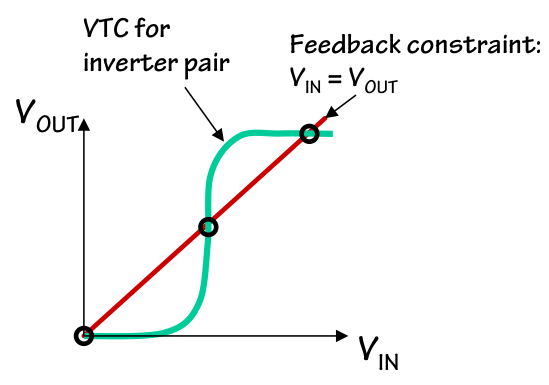

While it is true that the $X=0$ and $X=1$ states are the only solutions

admitted by this circuit in the logic domain, at the circuit level

the analysis is more complex. Consider the two-inverter cascade as a

single device whose voltage transfer characteristic looks like the green

curve shown to the left. This represents one constraint, expressed in

the voltage domain, on its input and output voltages $V_{IN}$ and $V_{OUT}$.

The feedback connection introduces a second constraint $V_{IN}=V_{OUT}$,

shown in red on the $V_{IN}$/$V_{OUT}$ curve. If we solve these two

equations that represent simultaneous constraints on $V_{IN}$ and $V_{OUT}$,

we find solutions wherever the two curves cross.

We do find solutions corresponding to valid $X=0$ and $X=1$ values in the

logic domain; however, the geometry of the intersecting curves is such that

they inevitably cross at a third point between these two solutions.

This third voltage-domain solution represents a problematic

unstable

equilibrium, and is dealt with at length in

Chapter 10.

This third equilibrium typically represents an invalid logic level, and

sequential circuits require a carefully designed engineering discipline

to avoid failures due to propagation of consequent invalid logic levels.

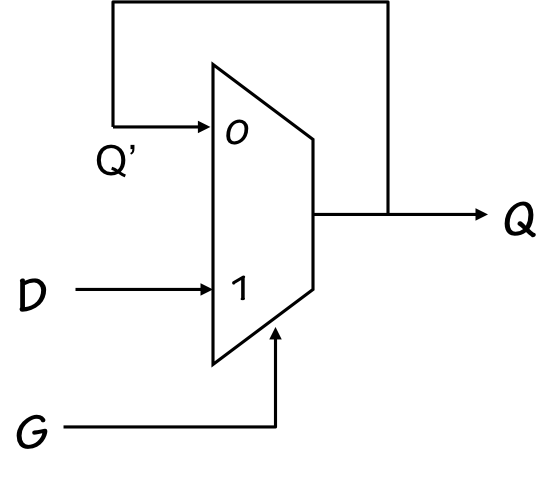

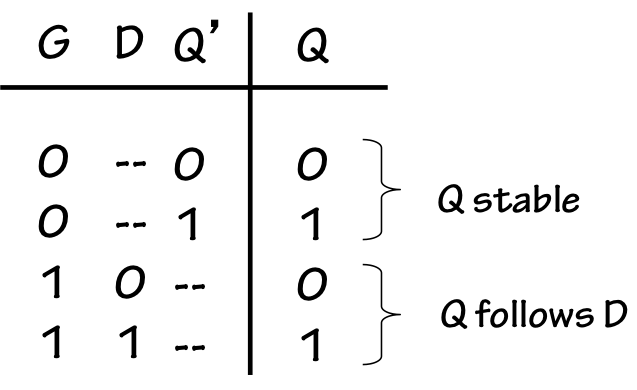

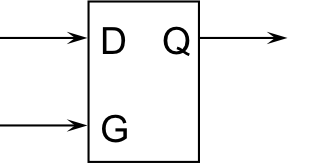

D Latch

8.2.1.1. D Latch

Although we may view the two-inverter loop as a device capable of

storing a bit of information, it is of little use unless we can

exercise some control over the stored bit.

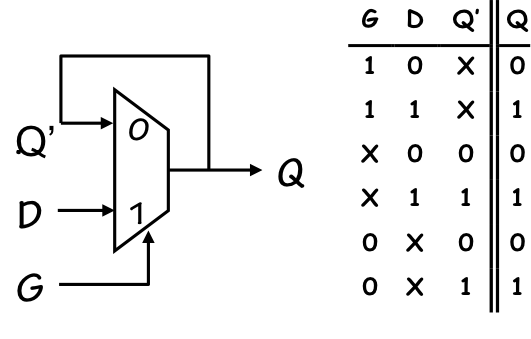

To effect such control, we will use a slightly more complicated

combinational device -- a lenient 2-way multiplexor -- in a similar

feedback loop as shown to the right.

This circuit has a data input $D$ and a control input $G$ (for "gate").

The logic-domain analysis of this circuit is, once again, appealingly

simple: when $G=1$, the logic value on the $D$ input is selected

as the output $Q$ of the device; when $G=0$, the feedback path

from the output $Q$ to the input $Q'$ is selected.

When $G=0$ there are again two stable solutions in the logic

domain: $Q=Q'=0$ and $Q=Q'=1$.

Our intention in this design is to use the $G$ input to switch between two modes

of operation detailed to the left: a $G=0$ mode where the $Q$ output reflects

a stored value, and a $G=1$ mode in which the value on $D$ follows a combinational

path to the $Q$ output.

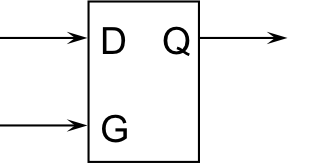

D Latch

D Latch

This device, called a

D Latch, thus behaves as a storage device when

$G=0$ and a "transparent" combinational circuit when $G=1$.

The intent is that a $1 \rightarrow 0$ transition on $G$ switches from transparent

to storage mode, capturing the data currently on $D$ as the newly stored value.

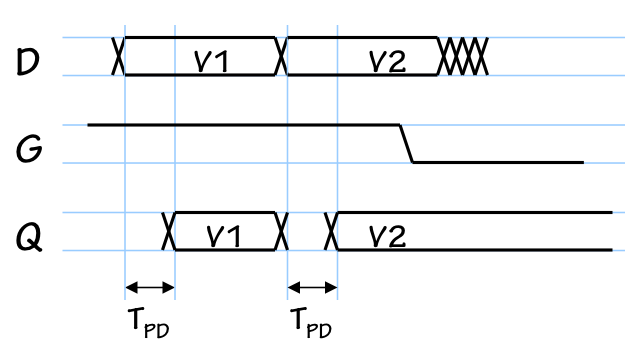

The timing diagram to the left depicts the behavior desired for our latch.

While $G=1$, the output $Q$ reflects the value on the $D$ input after a propagation

delay; changes in $D$ will cause corresponding changes in $Q$. If $G$ becomes

0 while some new value $V2$ is on $D$ (and hence $Q$), the latch will store

$V2$ so long as $G$ remains $0$.

Reliable Latch Operation

8.2.1.2. Reliable Latch Operation

Although capturing the $D$ value on a $1 \rightarrow 0$ transition of $G$

may seem intuitively simple, it confronts subtle obstacles that require

careful attention and for which

lenience plays a critical role.

The use of a non-lenient multiplexor in this circuit would imply

a period of undefined output after

any input change;

once $Q$ is allowed to become invalid, the $Q'$ input is also

invalid, and an invalidity loop may persist even after the $D$

and $G$ inputs are both valid.

Indeed, even a brief contamination of the Q output of the mux

allows invalid levels to circulate around the feedback loop, losing

the stored information; and the mux allows such contamination after

any input change.

Use of a lenient multiplexor, whose truth table appears to the right,

mitigates this problem by allowing a single input to change under certain

circumstances without contaminating the mux output.

The three circumstances when a mux input may change without contaminating

output validity are:

-

$G=1$, $D=v$ (for $v=0$ or $v=1$)

maintained as valid inputs for at least $t_{PD}$:

$Q=v$ despite changes in the $Q'$ input.

In this case, the $D$ input has been selected as the mux output value; thus

the value on the other data input is immaterial.

-

$D=Q'=v$ (for $v=0$ or $v=1$)

maintained as valid inputs for at least $t_{PD}$:

$Q=v$ despite changes in the $G$ input. In this case, the multiplexor is being

asked to choose between two identical data inputs, so the value on the select

input $G$ is immaterial.

-

$G=0$, $Q'=v$ (for $v=0$ or $v=1$)

maintained as valid inputs for at least $t_{PD}$:

$Q=v$ despite changes in the $D$ input.

In this case, the $Q'$ input has been selected as the mux output value; thus

the value on the other data input is immaterial.

Each of the above lenient-mux guarantees plays a crictical role in the

reliable behavior of our D latch. The first allows valid $G=1$ and $D$ inputs

to force a new value on $Q$, independently of its prior stored value.

The second allows us to change $G$ without contaminating the $Q$ output,

a requirement if we are to "latch" the current $Q$ output.

The third allows us to maintain a stored $Q$ value while $G=0$,

independently of changes on $D$.

There are additional constraints on the timing of our input signals that must be

enforced to ensure reliable latch operation.

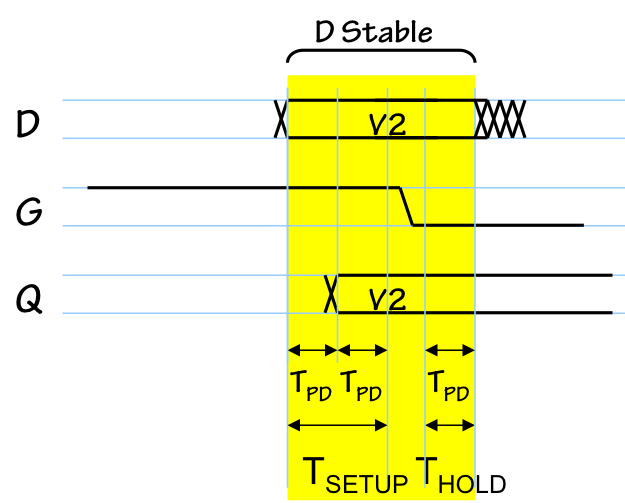

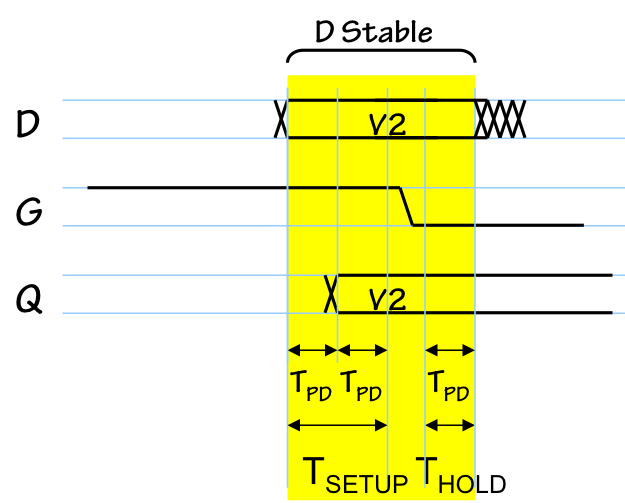

D Latch Timing

D Latch Timing

To explore the required timing discipline, lets consider the timing of a sequence of

input signals that guarantees the loading of some new value, $V2$, into a latch

made from a lenient multiplexor whose propagation delay is $t_{PD}$.

We assume that the latch is initially in some unknown state.

- The new value, $V2$, is applied to the $D$ input while holding $G=1$.

- After $D$ and $G$ have been valid for $t_{PD}$, the new value $V2$ appears

at the mux output $Q$ (and hence at the input $Q'$.

- After $D$ and $G$ have been valid for $2\cdot t_{PD}$, the $V2$ value

on $Q'$ will have been valid for at least $t_{PD}$.

Thus, the $D$ and $Q'$ inputs are now sufficient to guarantee a valid

$Q=V2$ independently of $G$.

- Continuing to hold $D=V2$, we now change $G$ to $0$.

$Q=Q'$ continues to hold a valid $V2$ during this change.

- After $D=V2$ has been valid for another $t_{PD}$, the $G=0$ and $Q'=Q$

inputs have been valid for a propagation delay and are hence sufficient

to maintain $Q=V2$ independently of $D$. The value $V2$

is now stored in the latch.

Note that, in order to guarantee that the new value $V2$ was reliably loaded

into the latch, we had to maintain a valid $D=V2$ input for a period extending

from at least $2\cdot t_{PD}$

prior to the $1 \rightarrow 0$

transition on $G$ through $t_{PD}$

following that transition.

Intuitively, we must guarantee that transitions on the $D$ and $G$ inputs

to our latch don't come at about the same time: such a race would create

a difficult decision problem of the sort discussed in

Chapter 10.

To avoid such difficulties, we establish a discipline for the

timing of changes on $D$ relative to the active transistion on $G$ for

our latch. In particular, we specify timing parameters $t_{SETUP}$

and $t_{HOLD}$ and require that $D$ must have been stable and valid for

an interval that includes

-

The setup time $t_{SETUP}$ before the transition;

-

The transition time during which the transition occurs; and

-

The hold time $t_{HOLD}$ after the transition;

The setup and hold times for our implementation of the latch are $2 \cdot t_{PD}$

and $t_{PD}$, respectively; although other implementations might have

different values for $t_{SETUP}$ and $t_{HOLD}$, they will typically enforce

the same form of constraint.

Combinational Cycle Problems

8.2.1.3. Combinational Cycle Problems

We might be tempted to try using a latch to store one bit of state for a sequential circuit, as shown

to the right.

Indeed, the latch is capable of holding a "current state" bit so long as its $G=0$;

that state is used to compute a "next state" bit applied to the latch's $D$ input.

However, loading this "next state" bit into the latch is problematic.

Clearly we must raise $G$ to a valid $1$, at least briefly, to load its

new value.

But for how long must $G$ remain $1$?

we note that, while $G=1$, our circuit has a

combinational cycle:

the combinational logic computes a new state bit, which propagates through

the latch to the combinational logic, which then computes a

new new state bit,

etc.

Signals are traveling around this cycle at an uncontrolled rate, and we

have no assurance of when (or even if) we can expect valid logic values.

For this reason, latches are rarely used directly as memory devices in

our digital circuits.

Rather, they are an essential building block for somewhat better behaved

flip flops that we will rely on as our basic storage element.

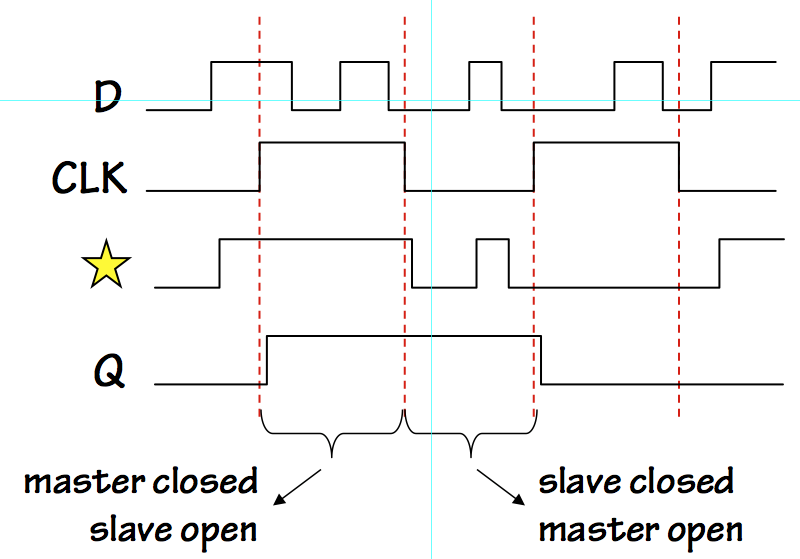

Edge-triggered Flip Flops

8.2.1.4. Edge-triggered Flip Flops

The difficulty in using latches as a memory device in our circuits is that,

in their "transparent" mode, they provide a combinational input-output path.

We can prevent such a path by cascading

two latches and ensuring

that they have opposite values on their $G$ inputs, as shown to the right.

The resulting device has a

clock input $CLK$ used to control the

flow of data from its $D$ input to its $Q$ output. For each value of $CLK$,

exactly one of the two latches -- the

master or the

slave --

is transparent; the other holds a stored value on its output.

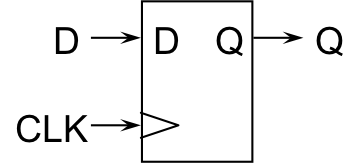

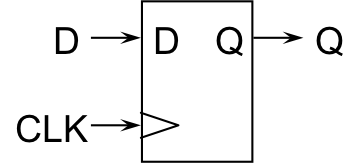

Flip Flop

Flip Flop

This device

is called an

edge-triggered or

master-slave flip flop

(or simply

flip flop or

flop)

and is depicted as shown on the left. The $CLK$ input triangle conventionally

represents the clock input to a

clocked device, a class of sequential

devices using edges on their clock inputs to specify timing of critical

events such as loading of new data.

We will build clocked devices using flip flops and combinational logic.

The flip flop shown above has the effect of loading new data from its $D$

input on a positive ($0 \rightarrow 1$) transition on its $CLK$ input.

The diagram to the right shows its behavior given a sequence of changes on its $CLK$

and $D$ inputs. As is typically the case, the $CLK$ input is a periodic square wave.

During the $CLK=1$ phase of its cycle, the master latch is

closed -- outputting

its stored value -- while the slave latch is in an

open or transparent

state, propagating its input value to its output via a combinational path.

During the $CLK=0$ phase, the master is open (propagating any changes on $D$

to the input of the slave) while the slave is closed, maintaining a constant

flip flop output value.

Note that on a positive $CLK$ transition the master latch goes from open to

closed, effectively latching the current data input as its stored value.

This value propagates through to the (transparent) slave and hence to the

flip flop $Q$ output.

The value is latched by the slave on the subsequent negative transition of

$CLK$, but the flipflop output remains unchanged since it matches the

slave input value.

The effect is that the flip flop output value reflects a single stored

bit, which is loaded from $D$ into the flip flop on each positive edge

of $CLK$.

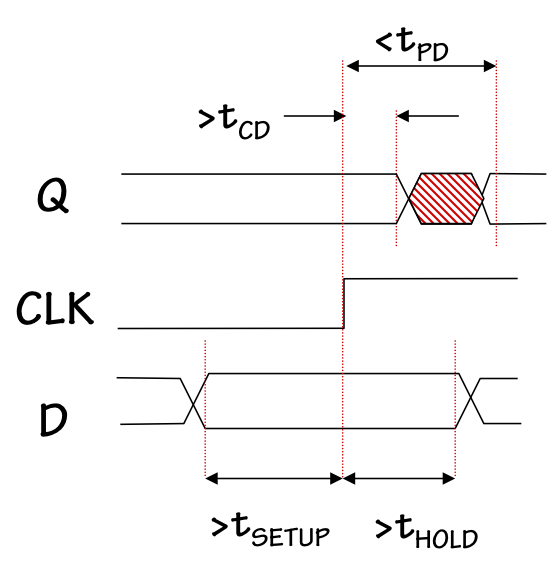

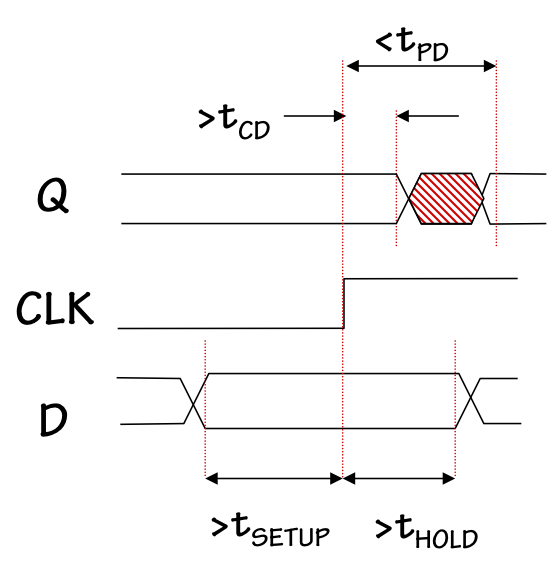

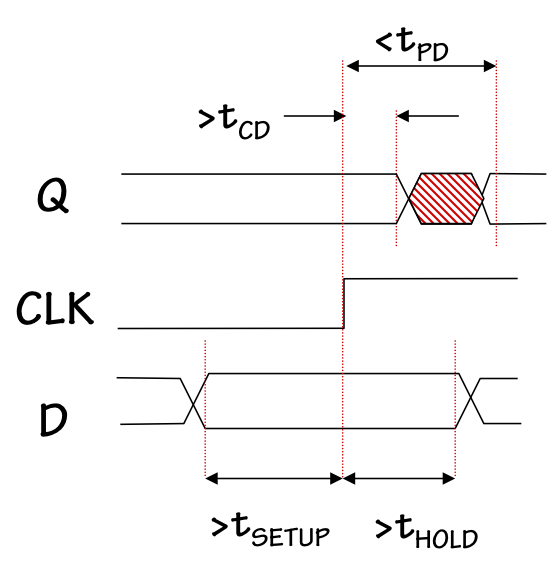

Flip flop timing

Flip flop timing

We can summarize the timing characteristics of the flipflop as shown in the

diagram to the right.

To load a new value, we again require that the $D$ input

remain stable and valid for an interval that includes prescribed

setup and hold times surrounding the active $CLK$ edge.

These values are chosen to ensure that the setup and hold times of

the component latches are met.

We also characterize the timing of the $Q$ output of the flip flop

by familiar

propagation and

contamination delays.

In contrast to the $t_{PD}$ and $t_{CD}$ of combinational devices,

however, for clocked devices we measure these intervals relative to

the active clock edge.

Thus, as depicted in the above diagram, the $Q$ output will maintain

its previous value for at least $t_{CD}$ following the start of an

active $CLK$ edge, and will present the new value no later than

$t_{PD}$ following that edge.

Of course, for reliable operation we must ensure that the timing of the

inputs to each latch in the flip flop obeys the setup and hold time

constraints specified by the latch.

The setup and hold time specifications for the flip flop must cover

the setup and hold time requirements of the master latch, which

ensures that the setup time requirement of the slave is met as well.

Slave Hold Time

Slave Hold Time

The hold time requirement of the slave, however, imposes a constraint

that is less easily controlled.

Meeting this constraint involves ensuring that on a

negative

transition of $CLK$, the value on the output of the master latch

(the circuit node marked with a star) remain

valid for the specified slave hold time.

Given that the master becomes transparent on this same clock edge,

a transition on this node may happen at about the time of this edge.

The only way to guarantee the sufficient hold time is to ensure that

the contamination delay of the master latch is sufficient to cover

the slave's hold time requirement.

Dynamic Discipline

8.3. Dynamic Discipline

Our introduction to the Digital Abstraction in

Chapter 5

deals with the embedding of an abstract digital domain of $1$s and $0$s in

the physical world of continuous variables. In this move from continuous

to discrete values, we observed the unavoidable consequence that not every

continuous voltage is a valid representation of a logic level, presenting the

problem of designing circuits whose outputs are guaranteed to be valid at

least during prescribed intervals. The

static discipline of

Section 5.3.1 assures that, for combinational circuits,

valid inputs lead to valid outputs after an appropriate propagation delay.

Our move to clocked sequential circuits complicates this picture by the

introduction of

time into our model. Wires now may carry a sequence

of valid values separated by periods of invalidity, and we require an

additional engineering discipline to reliably distinguish intervals of

validity and prevent invalid signals from propagating throughout our

circuits.

The setup and hold time constraints derived for our basic clocked

building block -- the flip flop -- provide one model for such an

additional engineering discipline, and the one that will be followed

in this course.

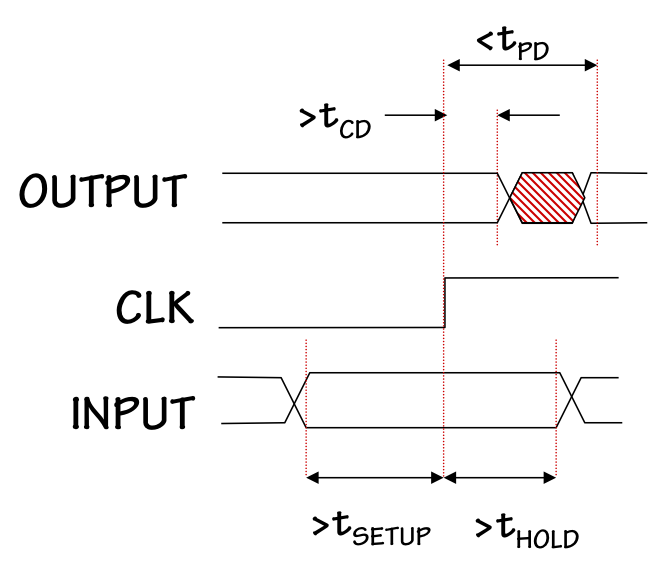

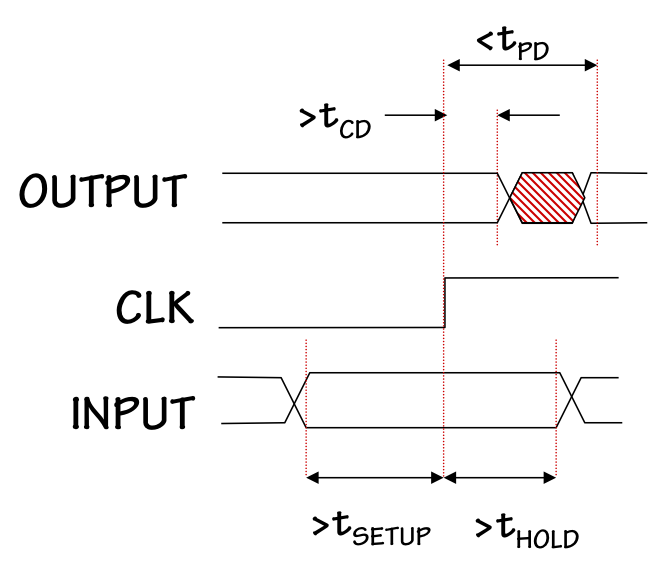

Dynamic Discipline

Dynamic Discipline

The

Dynamic Discipline, summarized in the timing diagram to the right,

requires that inputs to a clocked device be stable and valid for a time window

surrounding each active clock edge that includes a

setup time prior

to that edge and a

hold time following the edge.

If input changes conform to this restriction, output validity is guaranteed

outside of specified contamination and propoagation delays, measured from

the active clock edge (rather than from input changes, as in combinational

circuits).

We can build clocked sequential circuits of arbitrary complexity by combining flip flops

with combinational logic.

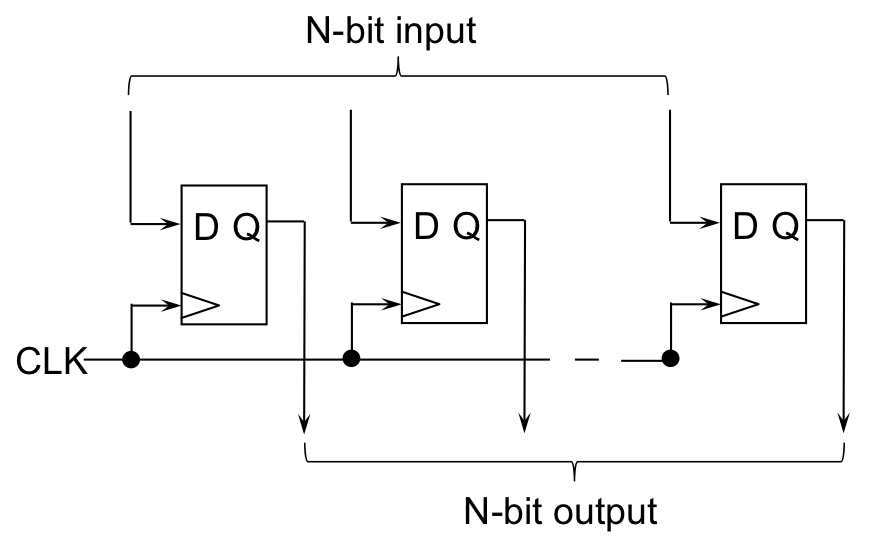

Registers

8.3.1. Registers

Often we combine $N$ flip flops sharing a common clock as shown to the left

to make an $N$-bit

register, a basic clocked storage device capable

holding a multi-bit datum.

All bits of a register are loaded on the same active

clock edge, and are subject to the same setup and hold time requirements

with respect to that edge. Register outputs appear simultaneously, again

subject to the contamination and propagation delay specifications from the

component flip flops.

N-bit Register

N-bit Register

Registers are denoted in our circuits by the symbol to the right; note

the annotations on the data input and output lines to show they represent

bundles of $N$ wires carrying $N$ bits simultaneously.

Adding logic to clocked devices

8.3.2. Adding logic to clocked devices

There are a variety of approaches to building complex sequential systems.

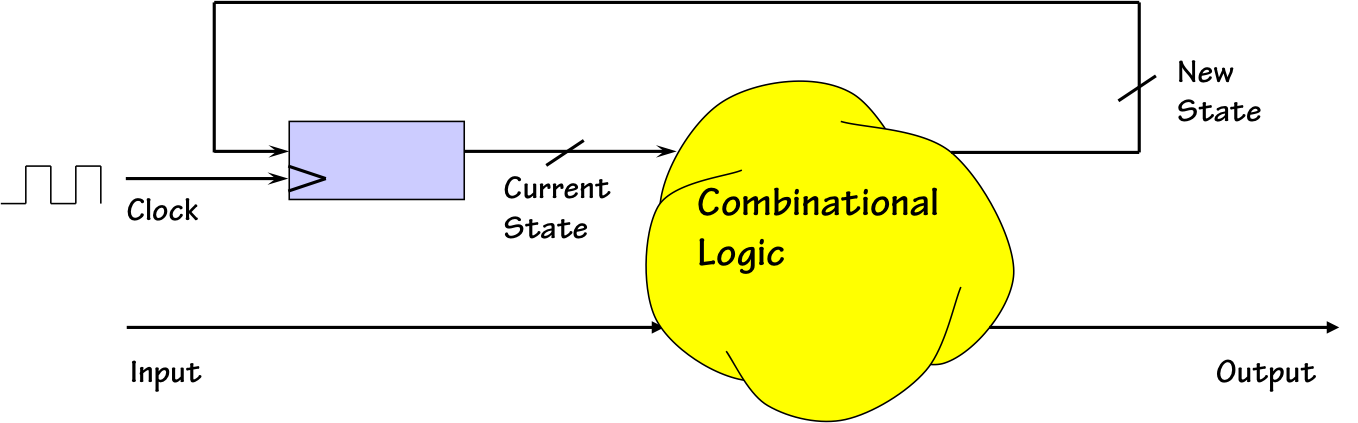

Finite State Machine

Finite State Machine

A simple approach suggested in

Section 8.1 is to use a single multibit register

to hold the entire system state, as shown to the left.

This approach is convenient for certain sequential circuit applications, and

is the basis for the

Finite State Machine abstraction discussed in

Chapter 9.

The dynamic discipline imposed by the register in the above diagram requires

that its setup and hold time requirements, $t_{SETUP}$ and $t_{HOLD}$, be met.

Assume that the combinational logic has propagation delay $t_{PD/LOGIC}$ and contamination

delay $t_{CD/LOGIC}$, and the propagation and contamination delay specifications

for the register are $t_{PD/REG}$ and $t_{CD/REG}$ respectively.

Then the dynamic discipline requires that

- $t_{PD/REG} + t_{PD/LOGIC} + t_{SETUP}$ be less than the

clock period, to assure that the new state data will meet the register

setup time requirement;

- $t_{CD/REG} + t_{CD/LOGIC} \ge t_{HOLD}$, to assure that the register

hold time requirement is met;

- The setup time for the input data is at least $t_{PD/LOGIC}+t_{SETUP}$,

to assure that changes in input data propagate to the register in time to

meet its setup time requirement; and

- The hold time requirement for the input data is at least

$t_{HOLD} - t_{CD/LOGIC}$ to assure that input value changes conform

to the register hold time requirements.

It is often more convenient to distribute state information of a complex

system among various subsystems, allowing the construction of such systems from

sequential components.

Orderly construction of systems with distributed state -- and management of the

exploding number of consequent setup and hold time requirements -- demands

the constraints of an additional engineering discipline.

While there are several alternatives, the simplest and most common of these

is the

single clock synchronous discipline presented in

Section 8.3.3.

Single Clock Synchronous Discipline

8.3.3. Single Clock Synchronous Discipline

A straightforward approach to engineering sequential systems of arbitrary

complexity is to use a single, shared, periodic clock signal to dictate

the timing of validity for all signals within the system.

Single Clock Synchronous System

Single Clock Synchronous System

We can build such systems from combinational logic and interspersed registers

as sketched to the right, so long as a few simple rules are followed.

The basic idea is that the active edges of a single clock signal dictates

timing of all register reloads throughout the system, and, consequently,

the timing of the validity of each register output. Each output typically

propagates through some combinational logic to another register,

where it must become valid in time to meet the target register's setup

time requirement prior to the

next active clock edge.

The clock period is then chosen to be sufficiently long to cover the

propagation delay and setup time of each such path, assuring that all

setup times within the system are met.

In general, the design of a single-clock synchronous system requires that

- Components are combinational devices and clocked devices (i.e., registers).

- The circuit contains no combinational cycles -- every cyclic directed

path must go through at least one register (or other clocked device).

- A single clock input to the system directly drives the clock input of each

clocked component; no gates or logic may be imposed on clock signals.

- Every internal path (of the form $REG_{SOURCE} \rightarrow LOGIC \rightarrow REG_{TARGET}$)

has sufficient contamination delay to cover the hold time requirement of the target register.

- The period of the system clock is sufficiently long to cover the propagation delay along

every internal path (again of the form $REG_{SOURCE} \rightarrow LOGIC \rightarrow REG_{TARGET}$)

plus the setup time of the target register.

- Each input $IN$ to the system is subject to a setup time requirement sufficiently

long to guarantee that every path of the form $IN \rightarrow LOGIC \rightarrow REG_{TARGET}$

covers the propagation delay through $LOGIC$ plus the setup time of the target register.

The tedium of meeting internal hold time requirements can be mitigated by the use

of registers whose contamination delay is at least as great as their hold time

requirement, assuring that hold times are met in each path between registers.

Setup and hold time requirements for inputs to the system are dictated by the paths connecting

the inputs to registers, and the timing of system outputs by paths between these

outputs and internal registers.

Synchronous Hierarchy

8.3.4. Synchronous Hierarchy

The single-clock synchronous discipline allows, in principle, the use of

clocked sequential subsystems as components.

Clocked components may themselves follow the single-clock discipline in their

internal construction, allowing a hierarchical approach to the design of

complex systems.

Since all of our single-clock sequential circuits are constructed from

flip flops and combinational logic, a hierarchical design can always be

"flattened" by expanding each clocked component into a network of flip flops

and logic; if the single-clock discipline is uniformly followed by each

component, the expanded network will follow that discipline as well.

In practice, however, such flattening is rarely necessary. If appropriate

setup and hold time constraints are specified for each component, it

follows that meeting these constraints assures that the setup and hold

time constraints of each internal register are met as well.

It is this property that motivates our generalization of flip flops

(or, equivalently, registers) to

clocked devices in our

single-clock rules.

Example: Sequential Circuit Timing

8.3.5. Example: Sequential Circuit Timing

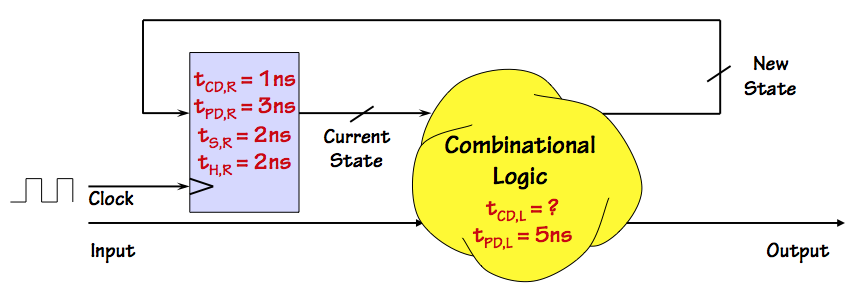

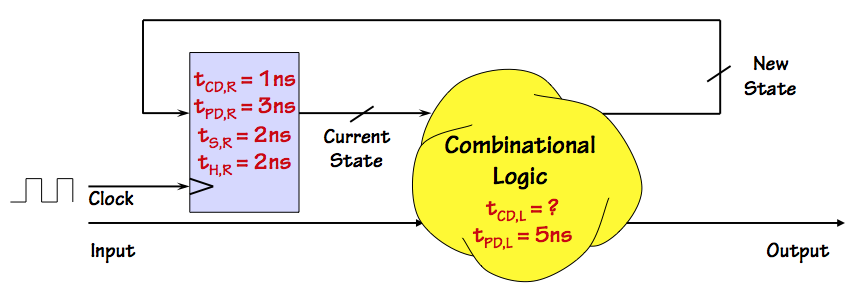

Clocked device example

Clocked device example

Consider a clocked device constructed from a register and some combinational logic, as diagrammed to

the right. The register specifies propagation and contamination delays of 3 and 1 ns, respectively, and requires setup and hold times of 2 ns each; the combinational logic has a propagation delay of 5 ns.

We assume a periodic clock input whose active (positive) clock edges occur every $t_{CLK}$ ns.

Given these specifications, meeting the registers setup and hold times imposes the following constraints on the timing of our device:

- The feedback path from the register output through the combinational logic

to the register input must meet the 2 ns register hold time requirement.

This requires that the cumulative contamination delay around this path

$t_{CD,R}+t_{CD,L}$ be

at least 2 ns, requiring at least 1 ns of contamination delay for the combinational logic.

Unless this requirement is met, we can't expect the circuit to operate reliably.

- In order to meet the setup time requirement along this same feedback path,

the clock period $t_{CLK}$ must be long enough to include the cumulative propagation delays of the register and combinational logic as well as the specified register setup time.

Thus $t_{CLK} \ge t_{PD,R}+t_{PD,L}+t_{S,R} = 10 ns$.

The maximum clock frequency is thus $1/t_{CLK}$ or 100 MHz.

- The path from the Input through the combinational logic to the register must meet the register

setup and hold time requirements. To assure this, our device specifies required setup and hold times

for the Input line relative to active edges of the supplied clock of

$t_S = t_{PD,L}+t_{S,R} = 7ns$ and $t_H = t_{H,R} - t_{CD,L} = 1 ns$ respectively (assuming

the minimum $t_{CD,L}$ of 1 ns).

Non-CMOS Memory

8.4. Non-CMOS Memory

While the CMOS-based flip flops and registers described in section

Section 8.2 are

well suited to temporary storage of modest-sized digital values (such as state information),

other technologies are widely used for larger-scale storage requirements.

Certain of these (such as the Dynamic RAM used for computer main memory)

are

volatile, in that the information contained persists only so long

as the memory remains powered and operational. Other technologies such as magnetic

or optical disks are non-volatile, and useful for long-term and offline storage.

Most contemporary approaches to mass storage are much more sophisticated than

the glimpses given in the following sections might imply. Typically, modern

memory pushes bit storage density to the limit, and depends upon error correction

(of the sort described in

Section 3.4.3) to assure reliable storage.

RAM Arrays

8.4.1. RAM Arrays

The term

Random Access Memory or

RAM refers to a storage device architecture

containing some number of $N$-bit storage locations that are equally accessible, hence suitable

for situations in which they are accessed in random order.

Such designs are distinguished, for example from

serial-access memory devices (like

magnetic or paper tape) that prescribe a preferred order for accessing their stored data.

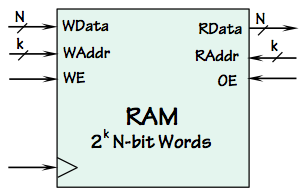

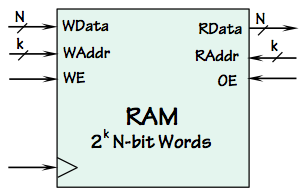

Random Access Memory

Random Access Memory

A representative model for a random-access memory component is diagrammed to the left.

It is capable of storing $2^k$ $N$-bit

words of binary data, for specified parameters

$N$ and $k$. It is organized (at least conceptually) as an array of $2^k$ locations,

each designated by an integer

address in the range $0 .. 2^k-1$.

It is typically a clocked device, hence the clock input on its lower left.

The three connections on the upper left constitute a

write port, and

consist of a $k$-bit

write address, an $N$-bit word of

write data,

and a

write enable control signal. If the write enable is asserted on an

active clock edge, the specified $N$ bits of data will be written into the location

specified by the write address.

The three connections on the upper right are a

read port, and specify

the address of an $N$-bit word to be read at the next active clock edge. The

read port may include an

output enable as shown here: a control input

that specifies whether the module is to perform a read operation and assert data

onto the

read data lines at the next active clock edge. The output enable

makes it convenient to cascade multiple RAM modules by connecting their $RData$

outputs.

RAM devices are often implemented as two-dimensional arrays of single-bit memory cells, sharing

a common addressing stucture much like that of the ROMs described in

Section 7.8.3.

Static RAM

8.4.1.1. Static RAM

Small fast memory arrays can be built entirely from CMOS gates and registers of the sort described

in

Section 8.3.1.

The design of such memory devices, however, is commonly optimized at the circuit level in ways

that violate CMOS rules in the interest of gains in performance and memory density. One such

family of memory devices are

Static RAMs or

SRAMs, named to distinguish

them from the

dynamic RAMs described in the next section.

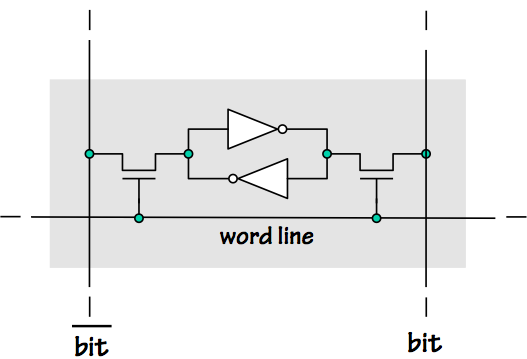

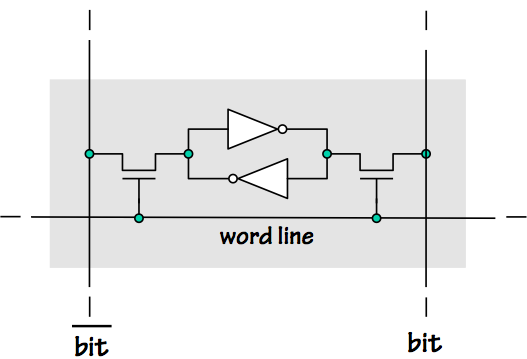

6T SRAM Cell

6T SRAM Cell

A typical SRAM consists of a two-dimensional array of six-transistor

cells like that shown on the right. Each row of cells shares

a

word line, asserted (driven positive) to select all cells

in that row for a read or write operation; each column shares

two

bit lines used to write or read a value to or from a cell

in a row selected by the asserted word line. Each cell consists of a

pair of cross-coupled inverters -- a simple bistable element -- whose

stored value and its complement are connected to the bit lines only

when the word line is asserted.

All cells in a row may be read by asserting the corresponding word line, driving the bit lines

of each column to voltages reflecting the 1s and 0s stored in each cell.

A cell may be written by driving the bit lines with a value and its complement, and momentarily

driving the word line. While violating CMOS rules (since opposing outputs are connected to the

same circuit node), appropriate choice of transistor sizing and drive parameters allows the

bit lines to simply overpower the value stored in the inverter pair, storing a new value.

Many variations and improvements to this SRAM cell design are possible.

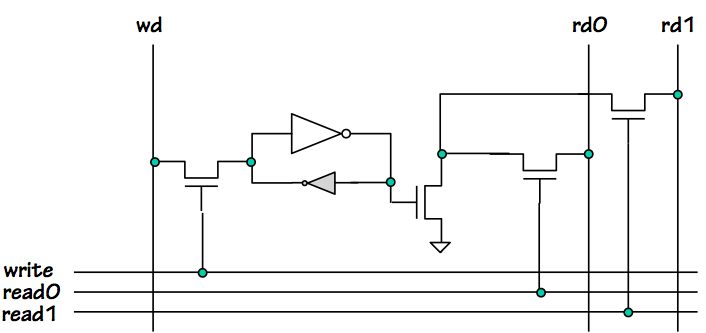

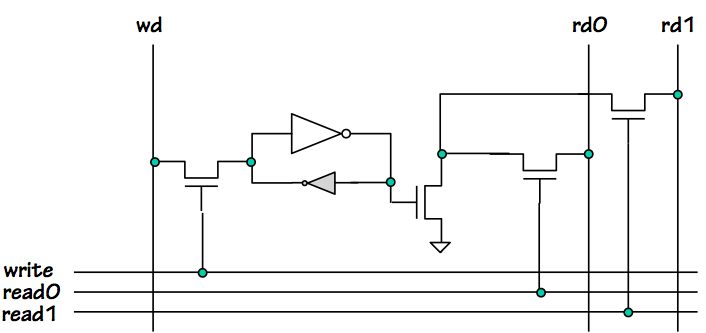

Multiport SRAM Cell

Multiport SRAM Cell

To the left is a cell for a SRAM array having two read ports and one write port, typical of the register files we will

be using in the next module of this course.

The cell uses a single bit line for a write operation; the use of assymmetric transistor sizes in the inverter pair

storing the bit allows its value to be overpowered from one end alone.

Each read port is supported by separate word and bit lines, allowing two independently-selected words to be

read simultaneously from the array during a single cycle.

Dynamic RAM

8.4.1.2. Dynamic RAM

Demand for large, cheap computer main memories has driven the development

of

Dynamic RAM or

DRAM technology to an extreme that minimizes the size of

each memory cell at the cost of sophisticated surrounding circuitry.

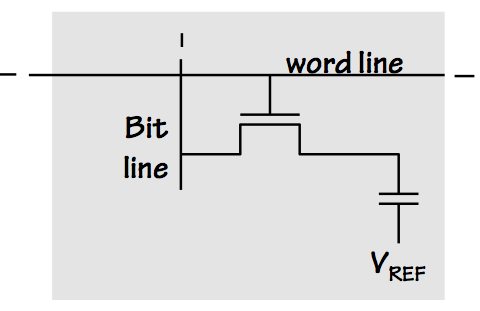

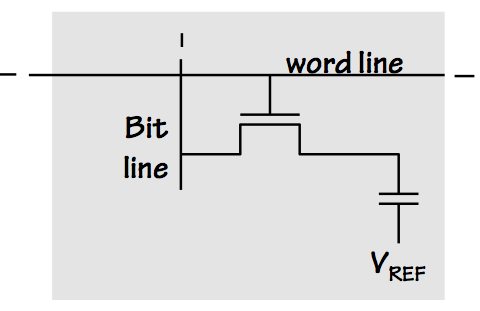

DRAM Cell

DRAM Cell

DRAM stores a single bit of information at each cell in the form of a charge on a

capacitor, using a structure like that shown to the right. The bottom terminal on the

capacitor is connected to a fixed reference voltage (such as ground), and the other terminal

is left "floating" (disconnected) so that no current flow will disturb the stored charge.

A single NFET is capable of momentarily connecting the floating end of the capacitor to a

vertical

bit line; this momentary connection is used both for setting the value

stored at the cell and reading the stored value.

The cell shown is again one of many arranged in a two-dimensional array, with vertically

aligned cells sharing a bit line and horizontal rows sharing word lines.

To store a value in a cell, the appropriate bit line is precharged to the appropriate

voltage and the voltage on the word line is raised briefly so that the NFET conducts

and charges the capacitor. Once the NFET returns to its usual non-conducting state,

the charge on the capacitor will be undisturbed by variation of the bit line voltage.

To read the value stored in the cell the word line is again asserted so that the

NFET briefly connects the bit line to the capacitor. In this case, a sensitive sense

amplifier connected to the bit line detects the effect of the connection on its voltage,

and determines whether the charge that had been stored on the capacitor represents a

zero or a one. The read operation is destructive (since it causes the stored charge

to be dissipated), so each read operation is immediately followed by a write operation

on the same cell to restore the stored information.

Because there is some leakage of the charge stored in each dynamic RAM cell, DRAMs

have to be periodically refreshed. This involves reading each cell and rewriting their

values, and leads to the "dynamic" in the name of this technology.

Magnetic and Optical Memories

8.4.2. Magnetic and Optical Memories

Mass memory technologies often involve significant mechanical components;

rotating optical and magnetic storage are popular contemporary examples.

These devices store bits as cells with persistent magnetic or optical state on a relatively

large surface, and use mechanical means to move an optical or magnetic head to

the appropriate position to read or record data. Although they can transfer

(read or write) data at high rates, they are decidedly not optimized for random

access: access to an arbitrary datum on a hard disk, for example, typically requires

a time on the order of ten milliseconds.

For this reason, rotating disk memory is typically used to access large blocks of

data stored in consecutive locations on the media.

Chapter Summary

8.5. Chapter Summary

The extension of our digital abstraction to include systems with

internal

state adds several key concepts:

- The notion that individual signal wires may contain a sequence

of potentially different logic values during the course of a

computation;

- The use of clock signals whose transitions dictate

the timing of transitions between valid logic values on signal wires;

- The need for a dynamic discipline to identify intervals

during which signal validity is guaranteed.

Because the design of basic elements with state from basic circuit

elements

is complex and error prone, we choose to carefully engineer a small

repertoire of

memory devices and restrict our design of

complex sequential systems to a mix of these and combinational devices

according to a carefully prescribed discipline. Our memory devices

include large

dynamic RAM arrays and magnetic/optical storage,

as well as

flip flops using carefully engineered feedback

loops and combinationial devices:

- A bistable latch may be constructed using a lenient

mulitplexor, and provides provably reliable storage so long as

an appropriate timing discipline is followed;

- Latches may be used to construct a flip flop, a

single-bit clocked storage device. Flip flops provide reliable

storage, again so long as an appropriate dynamic discipline is

followed.

- The dynamic discipline for clocked devices involves

- A clock signal, whose active (positive) edges

prescribes allowable times for transitions on other inputs;

- Setup and Hold times $t_s$ and $t_h$,

which establish a window surrounding each active clock transition

during which other inputs must be stable and valid; and

- Propagation and contamination delay specifications $t_{pd}$ and $t_{cd}$ on

each output, measured from the time of the active clock edge

to guarantee intervals of output validity.

- $N$ flip flops can be combined as an $N$-bit register, sharing a clock input;

- The single-clock synchronous discipline allows clocked circuit

elements to be interspersed with combinational logic, avoiding

combinational cycles and sharing a clock signal, to form new clocked components.

Although most of the systems in this subject follow the simple synchronous

single-clock discipline outlined here, there are plausible alternatives.

This subject is revisited briefly in

Section 11.8.