Combinational Logic

7. Combinational Logic

Armed with the abstract model of

combinational devices

outlined in

Chapter 5 and the concrete

implementation technology for simple gates of

Chapter 6,

we turn out attention to techniques for constructing combinational

circuits that perform arbitrarily complex useful functions.

To this end, we use the constructive property of combinational

devices outlined in

Section 5.3.2: an acyclic

circuit whose components are combinational devices is itself a

combinational device. That is, the behavior of such a circuit

can be described by the combination of a functional and timing

specification derived from the circuit topology and the component

specifications.

Functional Specifications

7.1. Functional Specifications

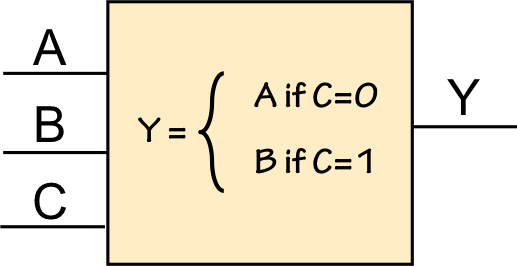

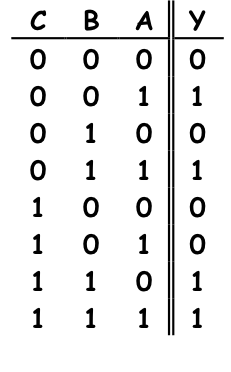

There are a variety of notations we can use to specify the functional

specification of a combinational device such as the 3-input, single-output

module shown to the right.

We might simply use a sentence or algorithmic description of each output

such as that shown in the box.

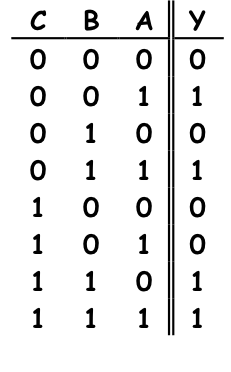

A more systematic specification is the

truth tables that have

been used in prior examples;

an equivalent truth table specification for this example is shown to the left.

A concise alternative to the truth table is a

Boolean expression:

$Y = \bar C \bar B A + \bar C B A + C B \bar A + C B A$

represents the same 3-input function as the truth table and informal

algorithmic specification.

In each case, the combinational device abstraction requires that the

functional description specify a logical ($0$ or $1$) value for each

combination of input values.

Boolean Expressions

7.2. Boolean Expressions

Boolean expressions are a ubiquitous notation in the engineering

of digital systems. They constitute a simple algebra for functions defined on

the domain of truth values ($0$ and $1$), and define three basic operations:

- Multiplication (logical AND): $A \cdot B$ or simply $A B$ represents

the logical conjunction of the values $A$ and $B$: the result is $1$

only if $A$ and $B$ are both $1$.

- Addition (logical OR): $A + B$ represents the logical disjunction

of the values $A$ and $B$; the result is $1$ if $A=1$ or $B=1$ or both.

- Negation (logical NOT or inversion): $\overline A$ represents the logical

inverse of $A$: $\overline A = 1$ if $A=0$, $\overline A = 0$ if $A = 1$.

The use of familiar algebraic notation -- multiplication and addition -- for

logical AND and OR operations takes a bit of time for the unitiated to assimilate.

The following list summarizes some properties of Boolean expressions that are

worth internalizing:

Boolean Identities

| OR rules: |

$a+1=1$ | $a+0=a$ |

|

$a+a = a$ |

| AND rules: |

$a \cdot 1=a$ | $a \cdot 0=0$ |

|

$a \cdot a = a$ |

| Commutativity: |

$a+b=b+a$ | $a \cdot b = b \cdot a$ |

| Associativity: |

$(a+b)+c=a+(b+c)$ |

|

$(a \cdot b) \cdot c = a \cdot (b \cdot c)$ |

| Distributivity: |

$a \cdot (b + c) = a \cdot b + a \cdot c$ |

|

$a+b \cdot c = (a+b)\cdot(a+c)$ |

| Complements: |

$a + \overline a = 1$ |

$a \cdot \overline a = 0$ |

|

$\overline{\overline a} = a$ |

| Absorption: |

$a + a \cdot b = a$ |

$a + \overline a \cdot b = a + b$ |

|

$a \cdot (a+b)=a$ |

$a \cdot (\overline a + b) = ab$ |

| Reduction: |

$a\cdot b + \overline a \cdot b = b$ |

$(a+b)\cdot(\overline a + b) = b$ |

DeMorgan's

Law: |

$\overline a + \overline b = \overline{a \cdot b}$ |

$\overline a \cdot \overline b = \overline{a+b}$ |

As the identities in the above table shows, there are many equivalent

ways of representing a given logic function as a Boolean expression,

and a variety of techniques for simplifying a Boolean expression or

converting it to a form that is convenient for one's purposes.

While there are many Boolean expressions that represent a given

Boolean function, there is essentially only one truth table

for each function: modulo permutation of inputs, a truth table

can be viewed as a

canonical representation.

One can verify the equivalence of two Boolean expressions with

$k$ variables by building truth tables that enumerate their values

for each of the $2^k$ combinations of variable values, and checking

that the tables are identical

Truth Table Arithmetic

7.3. Truth Table Arithmetic

The truth table for a $k$-input, single-output logic function

has $2^k$ rows, listing the single-bit output for each of the

$2^k$ potential combinations of input values. Each such $k$-input

truth table has the identical form: input values are listed, conventionally

in a systematic order corresponding to binary counting order;

truth tables for different $k$-input functions thus differ only in

the $2^k$ single-bit values in their output column.

There is a one-to-one correspondence between these truth tables

and the set of $k$-input logic functions. As there are $2^k$ output

bits that distinguish a particular $k$-input function, and each

output bit may be $0$ or $1$, it follows that the total number of

possible $k$-input functions is just $2^{2^k}$ -- precisely the

number of distinct $k$-input truth tables.

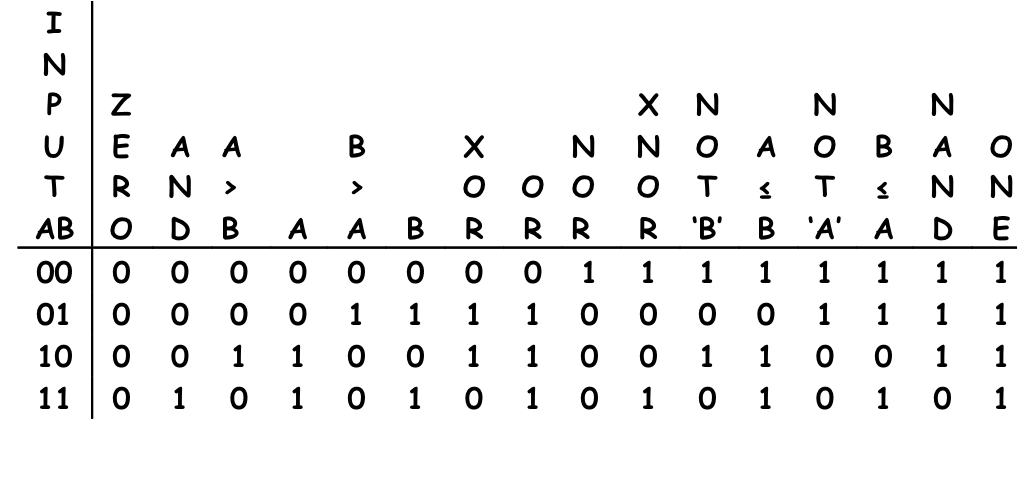

There are, for example, a total of $2^{2^2} = 16$ 2-input functions,

whose truth tables are summarized below:

Note that the full set of 2-input functions includes degenerate cases

of functions whose output is independent of one or both input values.

It is worth noting that, of these sixteen 2-input functions, only six

can be implemented directly as single CMOS gates: NOR(A,B)=$\overline{A+B}$

and NAND(A,B)=$\overline{A \cdot B}$, as well

as the degnerate cases $\overline A$, $\overline B$, $0$, and $1$.

Other 2-input functions must be synthesized using multiple CMOS gates

in a combinational circuit.

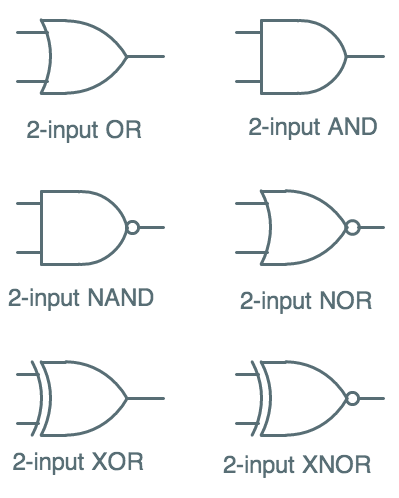

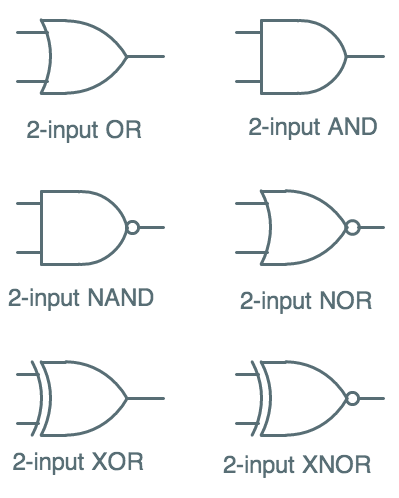

Gates and Gate Symbols

7.4. Gates and Gate Symbols

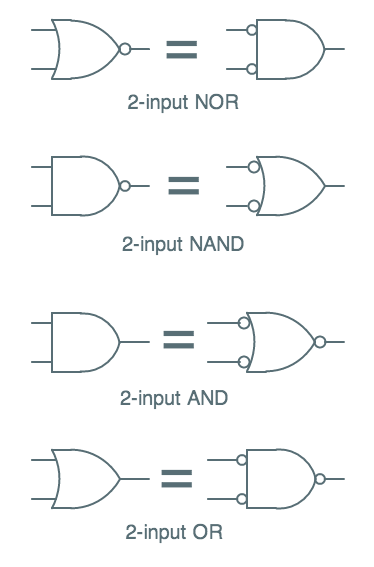

2-input gate symbols

2-input gate symbols

Circuit symbols for commonly-used 2-input combinational logic components

are shown to the right; some of these (NAND and NOR) we've already seen

in connection with their direct implementation as CMOS gates. The others

require multiple CMOS gates to implement.

The 2-input AND of $A$ and $B$ can be easily implented as a NAND gate followed

by an inverter, since $A \cdot B = \overline{\overline{A \cdot B}} = \overline{NAND(A,B)}$;

similarly, OR can be implemented as a CMOS NOR gate followed by an inverter.

The more complex $XOR(A,B) = A \cdot \overline{B} + \overline{A} \cdot B$

requires several CMOS gates to implement, as does its inverse $XNOR(A,B)$.

Note the consistent use of small circles --

"inversion bubbles" --

to indicate inversion of logic levels.

Universal Gates

7.5. Universal Gates

Although there are $2^k$ $k$-input logic functions we may wish to implement

as combinational devices, the ability to synthesize new devices as acyclic

circuits implies that we can begin with a small repertoire of basic gates

and design circuits using them to build arbitrary functionality. Indeed,

the observation that Boolean expressions are built using only three operations

(AND, OR, and NOT) implies that a starting toolkit containing only AND,

OR, and inverter modules is sufficient. Moreover, since we can synthesize

$k$-input AND and OR devices from circuits of 2-input gates, it follows that

an unlimited supply of 2-input AND and OR devices, along with inverters,

will allow us to

synthesize any logic functions we might wish. We term such a set

universal,

in that it contains all we need to implement arbitrary logic functions.

Happily, the 2-input NAND and NOR operations that are easily implemented

as single CMOS gates are each, in isolation, universal.

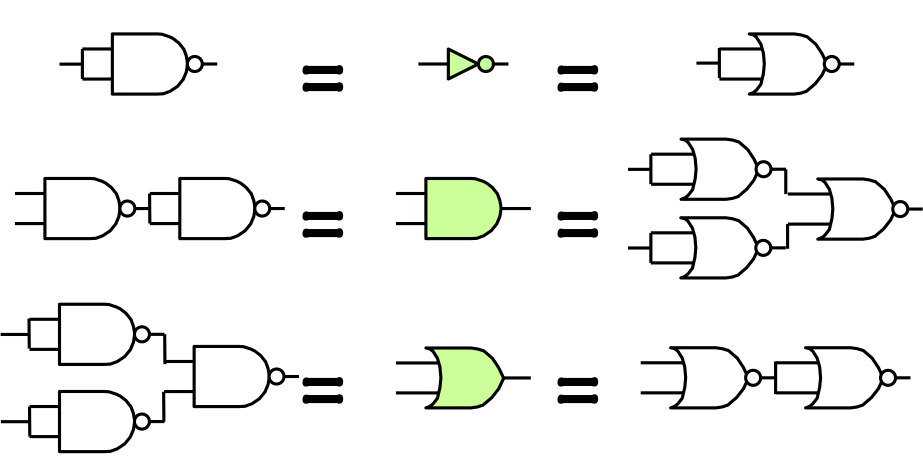

NAND, NOR Universality

NAND, NOR Universality

Given the universality of the ${AND, OR, NOT}$ set,

We can demonstrate the universality of ${NAND}$ or ${NOR}$ by showing

how to implement each of ${AND, OR, NOT}$ using only NAND or NOR gates,

as shown to the right.

From a logical standpoint, this implies that arbitrarily complex combinational

systems can be built from a parts inventory containing only 2-input NAND or NOR

gates.

Sum-of-Products Synthesis

7.6. Sum-of-Products Synthesis

It is straightforward to convert a truth table to an equivalent Boolean

expression in

sum-of-products form.

Such an expression takes the form of the Boolean sum (OR) of several

terms, each of which is the product of some set of (possibly inverted)

input variables.

Each such term $t_i$ corresponds to a line of the truth

table for which the output column contains $1$ -- called an

implicant

of the function, since $t_i = 1$

implies that the output is $1$.

If we reconsider the prior 3-input example, we note that the

four $1$s in the output column imply that the output $Y$ is $1$ for each of the input

combinations $ABC = 001, 011, 110, 111$.

For each of these, we construct an implicant term that is $1$ for precisely

the specified combination of input values, by including each input variable

in the term and inverting it (via the overbar notation) if its value is

$0$. The resulting sum-of-products expression is

$\bar C \bar B A + \bar C B A + C B \bar A + C B A$, an expression whose value is $1$

for precisely those combinations of input values for which the truth table specifies

$Y=1$.

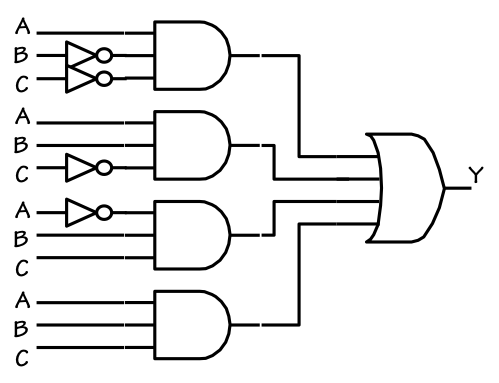

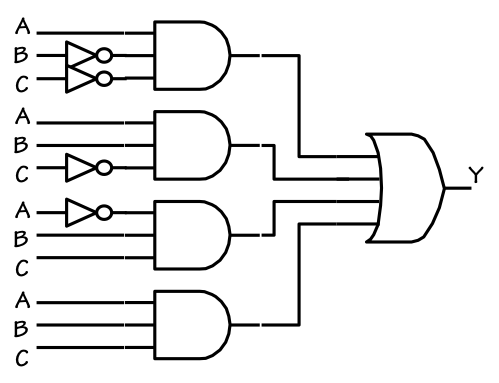

SOP Implementation

SOP Implementation

Given that Boolean expressions are built from using AND, OR, and NOT (inversion)

operations, it is tempting to synthesize circuits from Boolean expressions directly

using AND gates, OR gates, and inverters, as shown to the left.

Note that this approach generalizes to a systematic 3-tier structure

for arbitrary $k$-input functions:

- a layer of inverters to generate the necessary inverted inputs;

- A set of $N$ $k$-input AND-gates, where $N$ is the number of implicants.

Each AND gate computes the value of one term (implicant) of the sum-of-products

expression; and

- An $N$-input OR gate to sum the terms.

Although the direct sum-of-products implementation seems a straightforward

approach to implementation of arbitrary Boolean functions, it is rarely the

fastest or most efficient (in terms, say, of transistor count) of the

possible CMOS implementation techniques. This stems primarily from two

factors:

- CMOS gates are naturally inverting: AND and OR gates

use more transistors than NAND and NOR gates; optimized CMOS

implementations exploit the simpler inverting logic for circuit

simplicity, which is often at odds with the conceptual simplicity

of Boolean expressions built from AND/OR/NOT operations.

- Many Boolean functions have internal structure that can be

exploited to reduce implementation complexity, even using direct

AND/OR/NOT implementations. Such structure can often be

uncovered by manipulation of a Boolean expression to yield

a simpler, equivalent expression.

Tne number of transistors used in the above SOP implementation gives

a rough proxy for its implementation cost. Our example uses four

inverters (at two transistors each), four 3-input AND gates each

requiring 8 transistors, and one 4-input OR requiring 10 transistors.

The total transistor count for this circuit is thus 50; we will see

shortly that the same function can be implemented far more cheaply.

Boolean Simplification

7.6.1. Boolean Simplification

Although a direct sum-of-products representation for a Boolean function is

easy to derive systematically from a truth table, it rarely represents

the function's simplest or most convenient form.

We often can simplify the sum-of-product expressions by algebraic

manipulation, using the identites of

Section 7.2 and

other tools.

Consider, for example, the unsimplified Boolean expression for the

3-input function of the previous sections:

$Y = \bar C \bar B A + \bar C B A + C B \bar A + C B A$

Although this structure of the SOP implementation shown above

corresponds directly to the structure of this circuit, we can

find simpler expressions that suggest correspondingly simpler

implementations of the same function by algebraic manipulation

using the identities given above.

A particularly useful identity is the

reduction identity

$a \cdot b + a \cdot \bar b$, which generalizes to:

$\alpha X \beta + \alpha \bar X \beta= \alpha \beta$

where $\alpha$ and $\beta$ are arbitrary (possibly empty) Boolean subexpressions.

Thus we can simplify a Boolean expression by looking for pairs of terms that are identical

except for some variable $X$, which is inverted in one term but not in the other, and

by replacing the pair of terms by a single simpler term which omits the variable

that omits $X$.

Applying this reduction step to the 3-input Boolean expression above,

we notice that the terms $C B \bar A$ and $C B A$ match the pattern

and can be replaced by the simpler term $C B$, yielding

$Y = \bar C \bar B A + C B + \bar C B A$

Noticing that $\bar C \bar B A$ and $\bar C B A$ can be reduced

to $\bar C A$, we simply further to

$Y = \bar C A + C B$

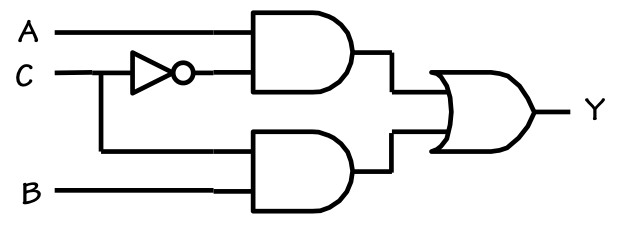

Simplified SOP circuit

Simplified SOP circuit

which is a simpler sum-of-products Boolean equation that is

equivalent to our original 4-term unreduced equation.

In fact it has two implicants rather than four

and each implicant is simpler, involving two variables rather than three.

Each of the terms of this expression implies a $1$ for

two input

combinations, allowing us to use fewer implicants in our simplified

expression. In fact each term of the simplified expression is a

prime implicant, meaning that no it is not subsumed by

any other (yet simpler) implicant for the function.

In addition to suggesting simpler implementations, the simplified expression

makes the function easier to understand: quick inspection reveals that $Y=A$

when $C=0$, but $Y=B$ when $C=1$. Although this characterization applies

equally to the equivalent 4-term unsimplified expression, that relationship

is much less obvious.

Based on this simplified Boolean expression, the direct sum-of-products

implementation shown to the right is correspondingly less complex

than that of our unsimplified 4-term SOP expression.

This implementation uses a single inverter (2 transistors), two

2-input ANDs (6 transistors each) and a single 2-input OR (6 transistors)

for a total transistor count of 20.

Repeated application of reduction steps together with other basic

identities (such as reordering variables in a term to recognise

reduction opportunities) is the approach taken by most software tools

for Boolean simplification.

Pushing Bubbles

7.6.2. Pushing Bubbles

Another of the Boolean identities listed in

Section 7.2 is

often referred to as

DeMargan's Law, and constitutes a useful

tool for transformation of Boolean expressions to more useful forms.

One statement of Demorgan's law is

$\overline A + \overline B = \overline{A \cdot B} = NAND(A,B)$:

that is, an OR with inverted inputs computes precisely the same value as an AND with

an inverted output. Conversely, it follows that

$NOR(A,B) = \overline{A + B} = \overline{A} \cdot \overline{B}$.

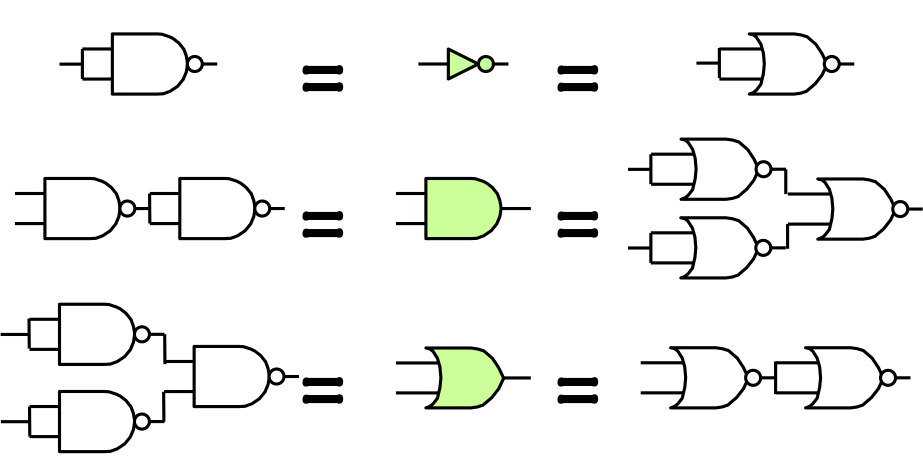

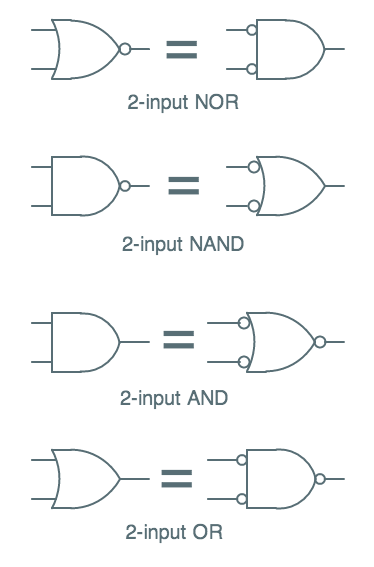

Demorganized gate symbols

Demorganized gate symbols

It is sometimes useful to reflect these equivalences in logic circuits

by using

"DeMorganized versions of circuit symbols, such as those

shown to the left.

Note that each row of the table shows two different circuit symbols

that perform the identical logic function -- indeed, they represent

precisely the same circuit implementation.

In each case, the two symbols reflect an application of DeMorgan's law:

inverting each input and output of an AND operation to convert it to

an OR (since $A \cdot B = \overline{\overline{A}+\overline{B}}$) or

inverting each input and output of an OR operation to convert it to

an AND (since $A + B = \overline{\overline{A} \cdot \overline{B}}$).

By judicious use of these equivalences we often can replace conceptual AND and OR operations

by the cheaper and faster NAND and NOR operations prefered in our

CMOS technology. The use of alternative symbols (together with our

understanding that pairs of inversion bubbles on the same wire cancel

each other) can make such transformations easier to recognise in our

circuit diagrams.

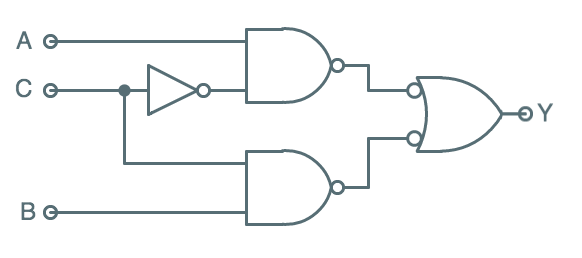

NAND-NAND SOP circuit

NAND-NAND SOP circuit

The diagram to the right shows a NAND/NAND implementation of the simplified

sum-of-products expression that has been our running example. Relative to

the AND/OR implementation, we have replace AND gates by NANDs (saving 2

transistors each) and used a Demorganized NAND gate instead of an OR

to add the terms (saving another 2 transistors). The total transistor count

of this implementation is 14.

Of course, it computes the same value $Y = \bar C A + C B$ as our original

50-transistor circuit.

Circuit Timing

7.7. Circuit Timing

As noted in

Section 6.4.4, we can bound the timing specifications

$t_{PD}$ and $t_{CD}$ of an acyclic circuit of combinational components by

considering cumulative delays along each input-to-output path through the

circuit.

| Device | $t_{PD}$ | $t_{CD}$ |

|---|

| Inverter | 2ns | 1ns |

| NAND | 3ns | 1ns |

| Circuit | 8ns | 2ns |

To illustrate, consider our 3-input NAND-NAND circuit implemented using

CMOS gates whose timing specifications are summarized to the left.

We may bound the propagation delay by the longest cumulative $t_{PD}$

along any input-output path; in this case, the constraining path involves

an inverter and two NAND gates for a total propagation delay of 8ns.

Similarly, we bound the contamination delay by the shortest cumulative

$t_{CD}$ along any input-output path, in this case involving 2 NAND

gates for a total contamination delay of 2ns.

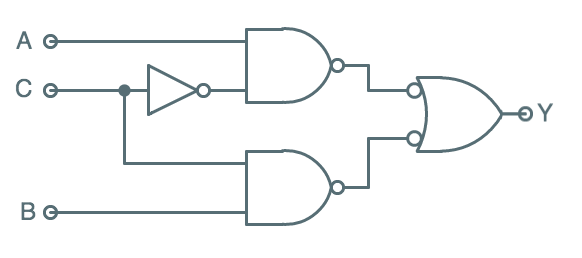

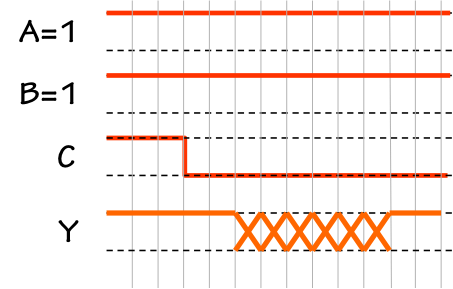

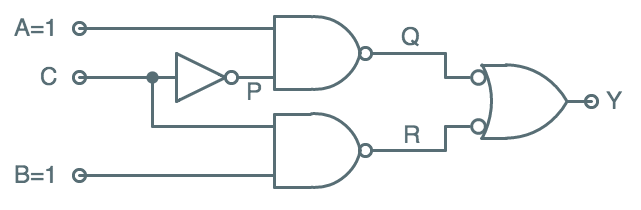

NAND-NAND Circuit Signals

NAND-NAND Circuit Signals

To explore the detailed timing of signals flowing through the circuit as the

result of an input change, consider an experiment where the $A$ and $B$ inputs

of our circuit are held to $1$ for an interval that includes a $1 \rightarrow 0$

transition on the $C$ input.

The diagram to the right includes new labels $P$, $Q$, and $R$ attached to internal

nodes of the circuit.

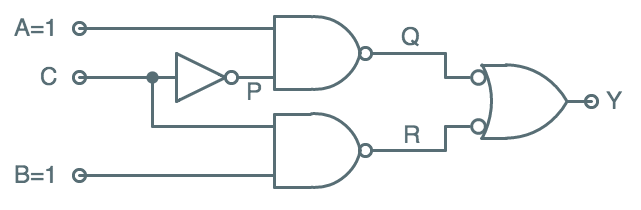

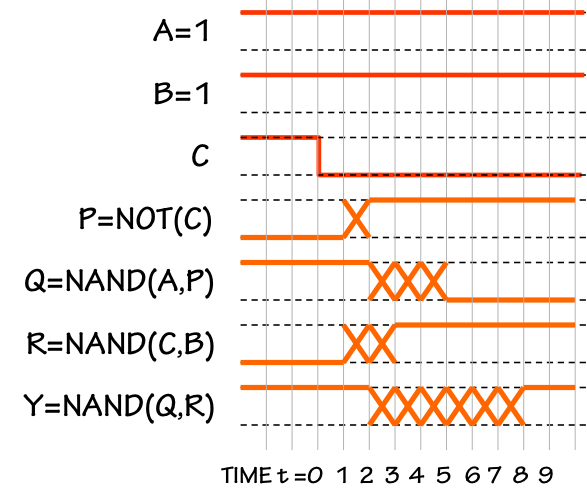

Signal Timing

Signal Timing

The diagram to the left details the timing of each signal in the circuit

as we maintain $A=B=1$ and apply an instantaneous $1 \rightarrow 0$ transition

on $C$ at time $t=0$.

Note that, prior to the $C$ transition, $A=B=C=1$ and all signals in the

circuit are at stable, valid values; the output $Y=1$, as dictated by

the functional specification of the circuit.

The $1 \rightarrow 0$ transition on $C$ at $t=0$ stimulates the propagation of

signal changes through the circuit, eventually affecting the output.

It is worth diving into the details of the timing of this signal flow

to understand the guarantees provided by the (lenient) CMOS gates in

our circuit:

- The inverter output $P$ remains $0$ for 1ns, due to the $t_{CD}=1ns$

inverter specification. It becomes a valid $1$ at $t=2$ -- 2ns following

the input transition -- as guaranteed by the inverter's $t_{PD}=2$ specification.

Note that during the intervening 1ns interval, the signal on $P$ is

unspecified -- it may be a valid $0$, a valid $1$, or invalid.

This interval of undetermined logic value is shown on the diagram by

a crosshatched X pattern.

- The output $R$ of the lower NAND gate remains $0$ for the 1ns NAND $t_{CD}$,

and becomes a valid $1$ after the 3ns NAND $t_{PD}$, with an intervening

2ns period of unspecified (possibly invalid) value.

- The output $Q$ of the upper NAND gate doesn't see an input change until

$t=1$, when its $P$ input becomes invalid. $Q$ remains a valid $1$ for an

additional 1ns contamination delay, after which it is contaminated.

$Q$ becomes a valid $0$ at $t=5$, the earliest time at which its inputs

have been valid for the 3ns NAND propagation delay.

- The output gate sees $R$ go invalid at $t=1$, but maintains a valid

$Y=1$ output for its 1ns contamination delay. Its $R$ input becomes a

valid $1$ at $t=3$, but its $Q$ input remains invalid until becoming

$0$ at $t=5$. Since a single $1$ input is not sufficient to determine

the output of even a lenient NAND gate, the output $Y$ cannot be

assumed to be valid until the 3ns propagation delay after both inputs

become valid. Thus, $Y=1$ at $t=8$, following a 6ns interval of unspecified

output value.

It is reassuring that, as the timing diagram shows, the output $Y$

remains valid for 2ns following the input transition and becomes

valid 8ns after that transition; this is consistent with the circuit's

$t_{CD}$ and $t_{PD}$ bounds computed earlier.

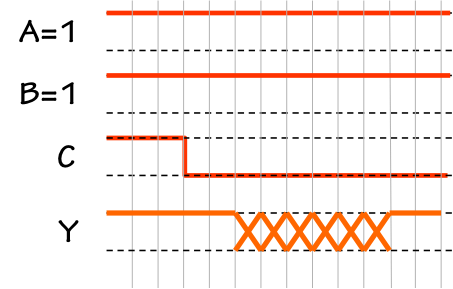

It may be bothersome, however, that the output of our circuit is unspecified

for an interval between the two periods of valid $1$s.

Given that $A=B=1$, the transition on $C$ does not affect the value of

$Y = \bar C A + C B$, and we might ask that the output remain a valid $1$

during this transition.

Non-lenient behavior

Non-lenient behavior

During the unspecified period, however, the output of our non-lenient

device may become a valid $0$, or even vacillate

between $0$ and $1$ several times, before settling back to its final value

of $1$.

Such anomalies are often referred to as

glitches or

hazards.

The fact that the use of lenient components does not guarantee

lenience of acyclic circuits built from them is annoying, but usually

not problematic.

In fact this device is a valid combinational device (for which

any

input change contaminates the output value for a propagation delay) but

not a

lenient combinational device (whose output remains valid

despite changes in irrelevent inputs).

For reasons explored in the next Chapter, reliable digital systems

require a timing discipline that makes signal values significant only

during prescribed intervals, allowing transient periods of invalidity

during which they may make transitions. A simple such discipline

is described in

Section 8.3.3.

Lenient Circuits

7.7.1. Lenient Circuits

In certain important applications, however, lenience of a combinational

component is critical. Suppose we had an application that requires

a

lenient device that computes $Y = \bar C A + C B$?

We know that single CMOS gates are lenient, but a bit of analysis

convinces us that this function cannot be implemented as a single

CMOS gate; hence we must resort to a circuit of CMOS components.

Fortunately, it is possible -- at some additional engineering and

hardware cost -- to design acyclic circuits of lenient components

that are themselves lenient combinational devices.

In general, non-lenience of combinational circuits stems from

the dependence of an output on any of several input-output propagation

paths. In the case of our 3-input NAND-NAND circuit, observe

that for $C=1$ the path holding the output $Y=1$ involves circuit

nodes $C=1 \rightarrow R=0 \rightarrow Y = 1$; when $C=0$,

the alternative path $C=0 \rightarrow P=1 \rightarrow Q=0 \rightarrow Y=1$

forces the output to be $1$.

Following the $1 \rightarrow 0$ transition of $C$, the former path

is disabled (no longer forcing $Y=1$) and the latter path is enabled

(forcing $Y=1$), but the timing of these two events is not strictly

controlled. Hence there is a period during which neither path may

be active, and the value of $Y$ is hence undetermined.

Using the terminology of

Section 7.6,

our circuit computes the value $Y = \bar C A + C B$ via two

implicants,

$C A$ and $\bar C B$, computed by separate paths and combined in the

final logical OR (using a Demorganized NAND).

The $C$ transistion switches responsibility for holding $Y=1$ from one

path to the other, effectivly selecting whether the $A$ input or the $B$

input should be taken as the output value $Y$. In our test case,

$A=B=1$ rendering the output value independent of which path is

selected;

however, there is no single path in our circuit which forces $Y=1$

when $A=B=1$.

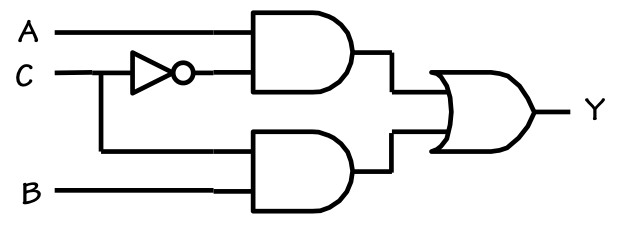

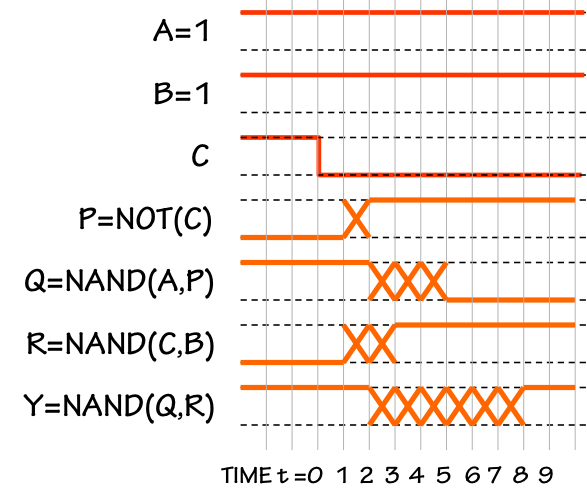

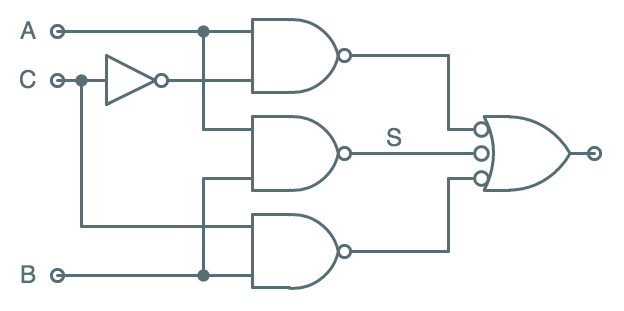

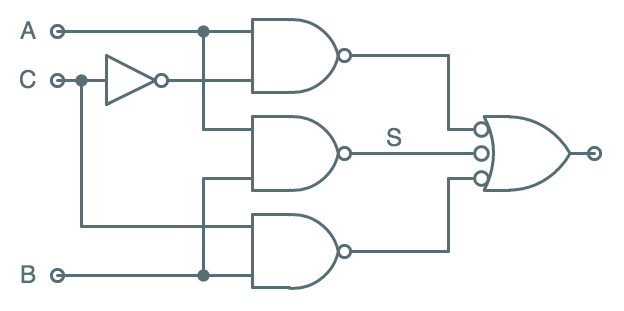

Lenient NAND-NAND Circuit

Lenient NAND-NAND Circuit

We can address this problem by adding a path representing a third

implicant, $A B$, to the circuit. The circuit shown to the right

uses three NAND gates to compute inverted versions of the three

implicants $A \bar C$, $A B$, and $C B$, and the final 3-input

NAND computes their sum. The resulting value is $Y = A \bar C + A B + C B$,

which is logically equivalent to our simplified $Y = A \bar C + C B$;

however, now there is a path dedicated to ensuring $Y=1$ for each

of three (rather than two) implicants.

This approach can be generalized to the implementation

of lenient combinationial circuits to compute arbitrary

Boolean expressions.

In the general case, a sum-of-products implementation using

lenient components will be lenient if it includes logic representing

every

prime implicant of the function.

Fan-In and Delay

7.7.2. Fan-In and Delay

Although the CMOS gate examples have focused on 2-input NAND and NOR

gates, we can of course implement many functions with more inputs --

higher

fan-in -- as single CMOS gates.

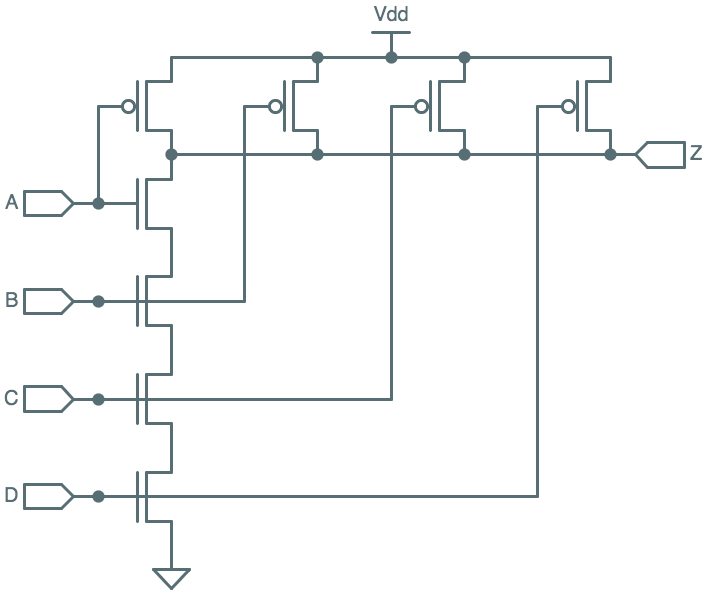

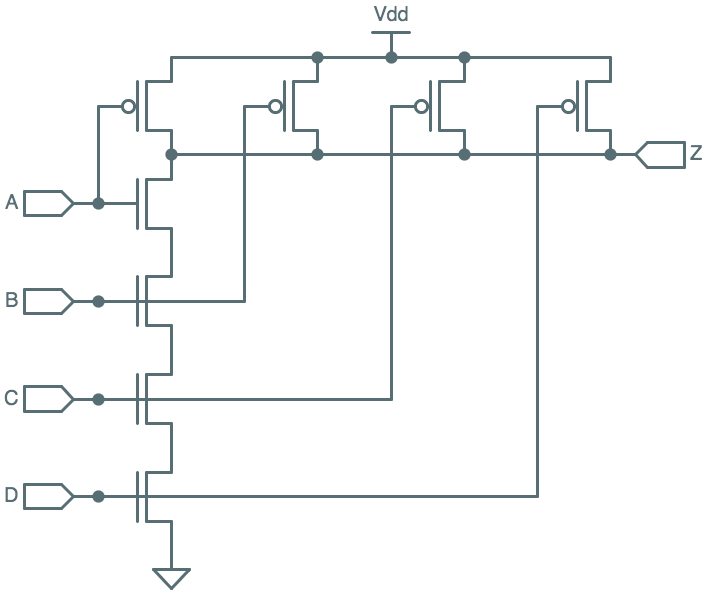

4-input NAND gate

4-input NAND gate

For example, the diagram on the right shows the straightforward extension of our CMOS NAND

gate to 4 inputs, by including additional PFETs and NFETs gated by the new inputs to the

parallel and series chains of the pullup and pulldown circuits.

While this approach can in theory be extended to single CMOS gates of arbitrarily many inputs,

the performance of CMOS gates degrades with increasing fan-in due to electrical loading.

In practice, it is typically preferable to implement functions of more than about four

inputs as circuits of smaller gates.

Certain common logical functions like AND, OR, and XOR offer a variety of

alternative approaches to large-fan-in circuit design. Each of these functions $F$

have the property that $F(a_1,...,a_k) = F(a_1, F(a_2, ..., a_k))$, suggesting

a strategy for repeatedly using 2-input gates to reduce the fan-in requirement by one.

But we may also observe that for each such function $F$,

$F(a_1,...,a_k) = F(F(a_1, ..., a_j), F(a_{j+1}, ..., a_k))$: we may partition

the $k$ arguments into multiple sub-operations, and employ a divide-and-conquer

approach to their combination.

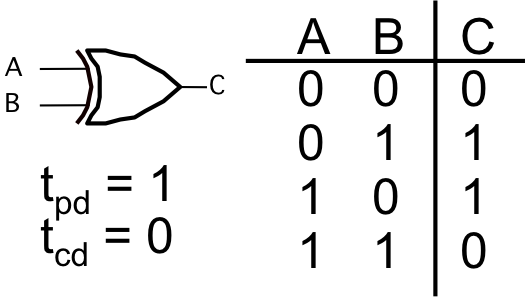

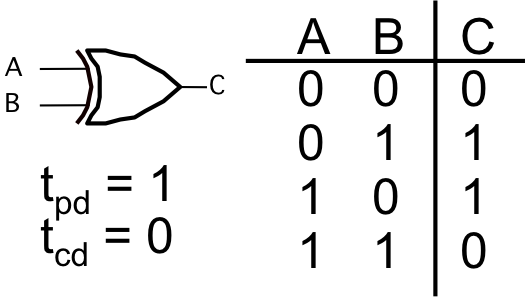

2-input XOR

2-input XOR

Suppose, for example, we have a 2-input XOR gate shown on the left.

Note from the truth table that the XOR function has the value $1$ if and only if

an

odd number of its inputs are $1$, a function that extends in a

straightforward way to arbitrarily many inputs and that has the properties

described for $F$ above. We desire to implement $XOR(a_1, ..., a_N)$ for

arbitrary fan-in, a function that returns $1$ if the number of $1$s among its $N$

inputs is odd. This function, sometimes called

odd parity, is useful

for error detection techniques such as those discussed in

Section 3.4.

The observation that

$XOR(a_1,...,a_k) = XOR(a_1, XOR(a_2, ..., a_k))$

suggests that we can compute $XOR(a_1, ..., a_N)$ by the circuit shown to

the right, in which each of the two-input XOR gates combines a single

input with the cumulative XORs from the gates to its left.

While this circuit works correctly, we note that the longest input-output

path goes through all $N-1$ of the component 2-input gates, yielding a

propagation delay that grows in proportion to the number of inputs.

While this may be an acceptable approach in some circumstances, we often

prefer an approach that minimizes the worst-case propagation delay of the

resulting circuit.

For

associative operations like $XOR$, we observe that

$XOR(a_1,...,a_k) = XOR(XOR(a_1, ..., a_j), XOR(a_{j+1}, ..., a_k))$

suggesting that we can reduce our $N$-input XOR to the XOR of the result

of two $N/2$-input XORs -- a step that halves the fan-in at the cost of

a single gate delay.

Repeated application of this divide-and-conquer step results in a

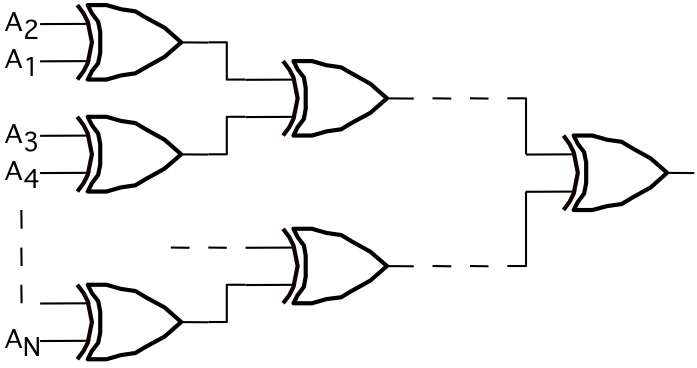

binary tree

structure as shown to the left. Note that a tree having $k$ levels of 2-input

components has a propagation delay proportional to $k$, but provides a fan-in

of $2^k$ inputs.

Thus an $N$-input XOR, for large fan-in $N$ can be computed by the tree

in time proportional to $log_2(N)$, an improvement over the linear

delay of the preceding approach.

Similar tree structures can be used to compute many other functions

whose extension to $N$ arguments is straightforward, including AND, OR,

and addition. Certain functions (like NAND and NOR) admit tree implementations,

but require some care due to their special properties (e.g., inversion).

Other functions don't decompose so nicely, and don't lend themselves

to tree implementations; an example is the $N$-input

majority

function, which returns $1$ if a majority of its inputs are $1$.

Systematic Implementation Techniques

7.8. Systematic Implementation Techniques

Typically the smallest, fastest, and most cost-effective implementation

of a complex Boolean function is a custom circuit designed and optimized

to compute that function. While there are many sophisticated techniques

and tools for designing such circuits, the customization process is

inherently expensive -- both in engineering and manufacturing costs.

For this reason, several synthesis approaches have been developed that

forego function-specific optimizations in order to allow the straightforward

implementation of an arbitrary $k$-input Boolean function by parameterizing

a fixed, function-generic hardware substrate. In this section we sample

several such approaches.

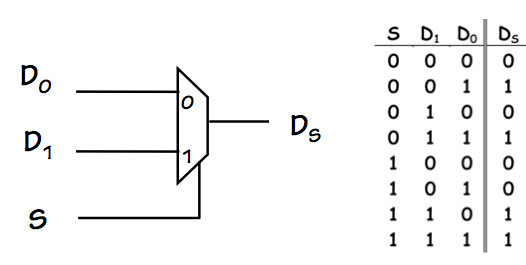

Multiplexors

7.8.1. Multiplexors

The three-input Boolean function used as a running example in this Chapter is

a a commonly-used component in our combinational repertoire: a 2-way

multiplexor

(or

Mux in the vernacular of logic design).

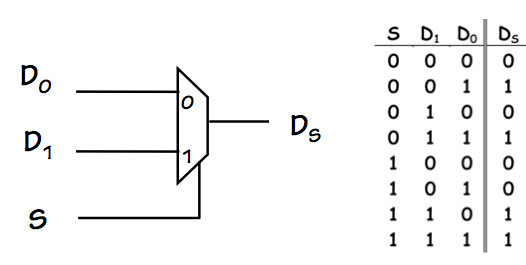

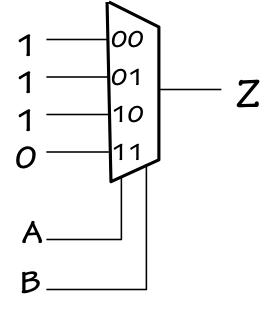

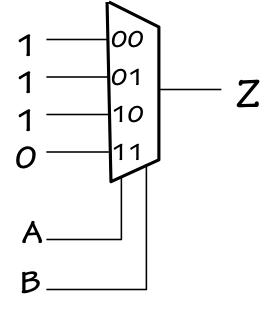

2-way Multiplexor

2-way Multiplexor

The logic symbol and truth table for a 2-way mux is shown to the right.

A useful model for its behavior is a 2-way logic-controlled switch:

it takes 2 independent data inputs $D_0$ and $D_1$, as well as a

select

input $S$; its output (after a propagation delay) is $D_0$ if $S=0$ or $D_1$ if $S=1$.

Muxes are useful for routing the flow of data through our combinational circuits

on the basis of

control signals applied to their select inputs; we will

see many examples of such uses in subsequent chapters.

As discussed in previous sections of this Chapter, the implementation of a multiplexor

may or may not be lenient; the example of section

Section 7.7.1 is,

in fact, a lenient 2-way multiplexor.

This device plays a key role in the implementation of memory devices in the next Chapter.

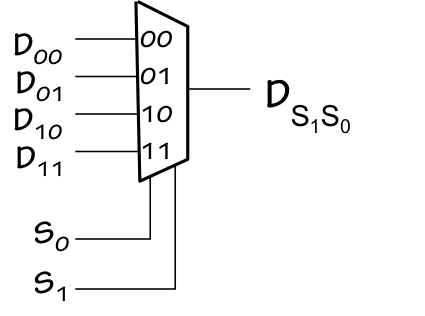

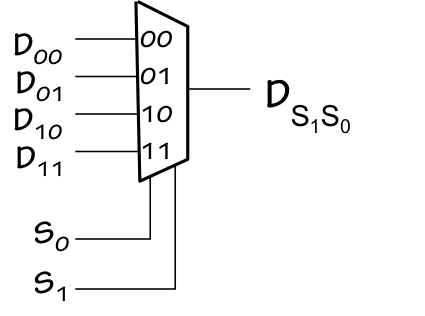

4-way Multiplexor

4-way Multiplexor

The multiplexor function can be generalized to $2^k$ inputs and $k$ select lines;

the diagram to the left shows a 4-way multiplexor, whose output is one of the four

data inputs as selected by the four possible combinations of inputs on the two

select lines.

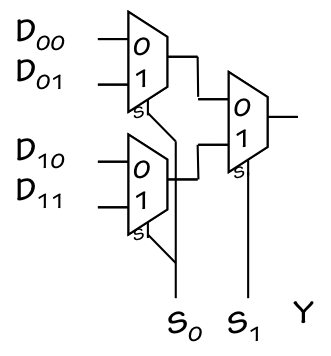

One way to implement a $2^k$-way multiplexor is to use a 2-way mux

selecting among the output of two $2^{k-1}$-way muxes, as illustrated

in the 4-way mux implementation shown to the right.

Lookup Table Synthesis

7.8.2. Lookup Table Synthesis

The ability of a multiplexor to select one of $2^k$ input values suggests

its use as a mechanism to perform

table lookup functions: based

on its select input, its output is one of the connected data values.

Mux-based NAND

Mux-based NAND

We might implement an arbitrary 2-input Boolean function, for example, by

use of a 4-way mux as shown to the left.

The Boolean inputs drive the select lines, and hence select one of the

four data inputs. If we connect the data inputs to constant $0$ and $1$

values corresponding to the output column of the Boolean function's

truth table, the supplied select inputs will effectively look up

the correct output from the supplied values. The function "programmed"

into this implementation is NAND, but by simply changing the constant values --

$0$s and $1$s implemented via

$V_{DD}$ and ground connections --

we can make this circuit compute any of the 16 2-input Boolean functions.

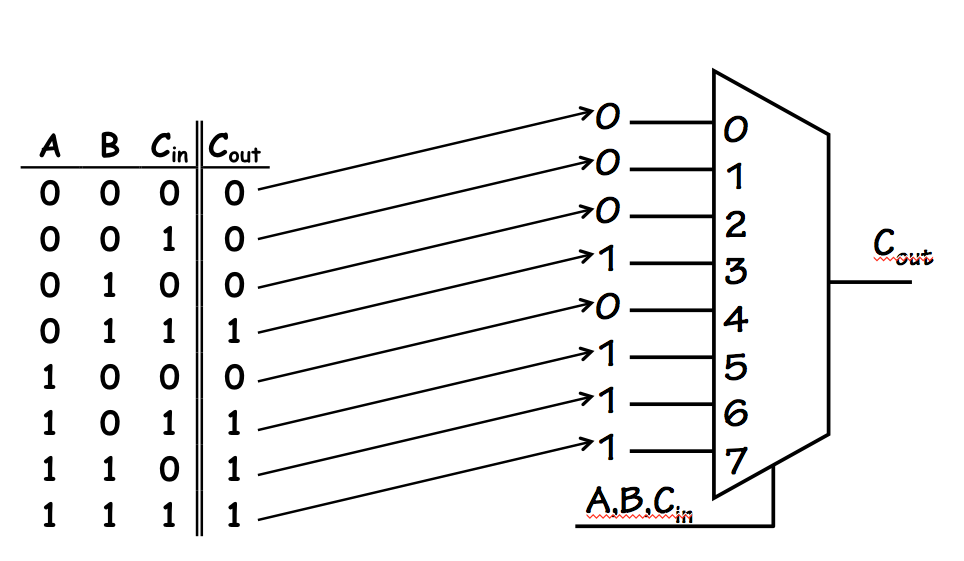

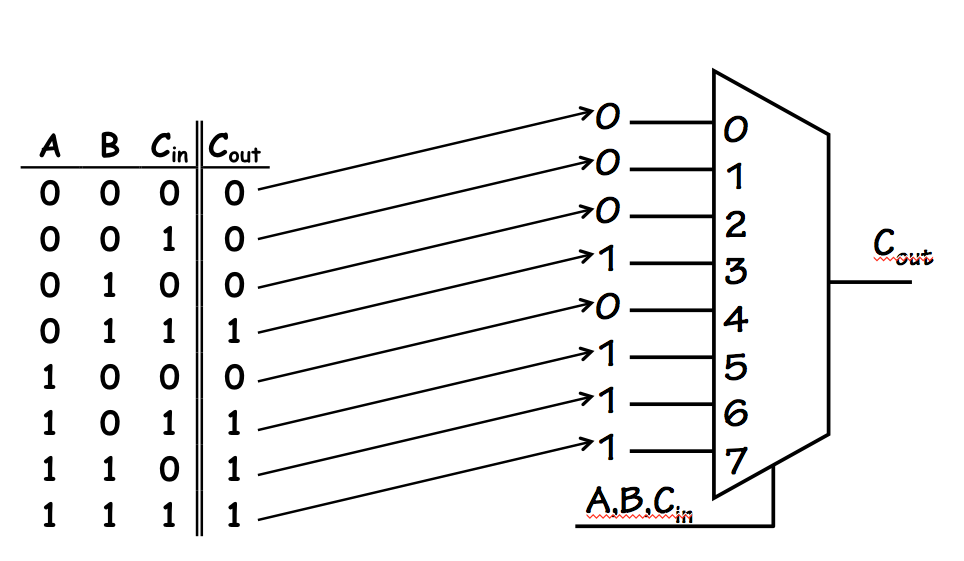

3-input table lookup

3-input table lookup

Using larger multiplexors, we can implement functions with more inputs.

The diagram to the right shows the implementation of a 3-input function -- the

carry output for a 1-bit

full adder device -- using an 8-way

multiplexor. Again, the mux simply chooses among the constant values

supplied (in accordance with a truth table) as its data inputs.

Table lookup approaches are attractive in applications where it is desirable

to isolate the hardware structure from the choice of the function to be implemented,

for example when that function might be frequently changed or is specified as

a customization parameter of an otherwise commodity hardware device.

Read-only Memories

7.8.3. Read-only Memories

When the number of inputs becomes large, the use of a simple mux-based approach

to table lookup is tedious: a 10-input function, for example, requires a 1024-way

multiplexor.

For this reason, table lookup approaches have evolved to space-efficient structures

that more effectively exploit the 2-dimensional layout constraints of the surface

of a silicon chip.

Such approaches are often called

read-only memories (ROMs),

and share with the mux-based lookup table the fact that the output

values are

programmed into the structure as data values

in locations corresponding to combinations of inputs. The various

input combinations may be viewed as

addresses of memory locations,

and the data values as the memory

contents.

This section provides a glimpse of a simple read-only memory technology

for the systematic implementation of arbitrary Boolean functions.

Although the technology is compatible with CMOS logic, it is noteworthy

that it differs from CMOS gate implementation in a number of important

ways -- among them are lenience and power consumption characteristics.

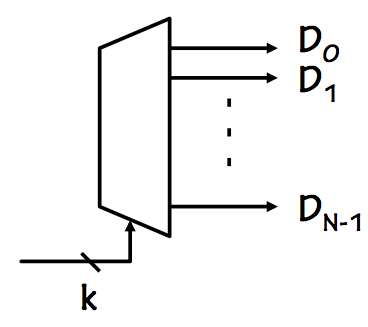

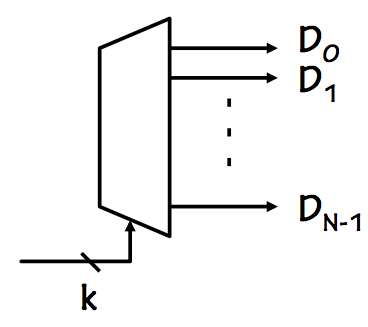

Decoders

7.8.3.1. Decoders

In order to expand our table lookup implementation to two dimensions, we

introduce another building block: a $2^k$-way

decoder.

Decoder

Decoder

The circuit symbol for a decoder is shown to the right.

It takes as input $k$ select lines, whose values select one of

$2^k$ output lines to be driven to a logical $1$; all unselected lines

remain at a logical $0$. Thus for any combination of valid inputs,

one and only one of the output lines will be $1$: the output lines

may be viewed a

decoded (or "

one-hot") representation

of the binary value supplied on the $k$ select inputs.

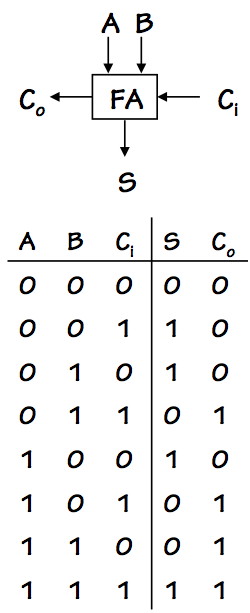

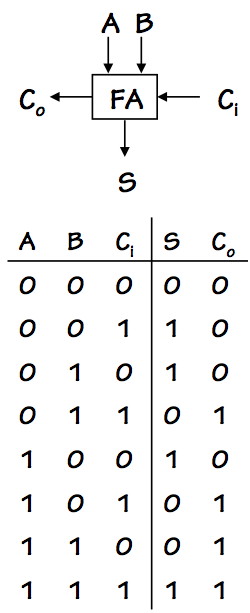

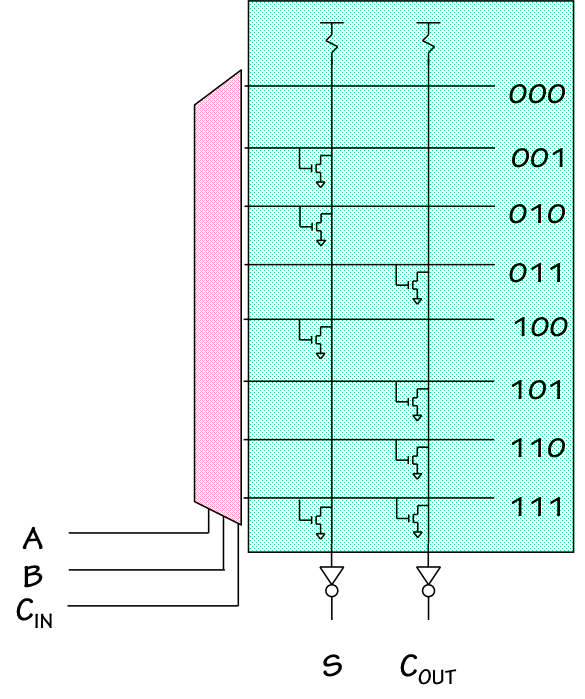

ROM-based Full Adder

7.8.3.2. ROM-based Full Adder

Full Adder

Full Adder

Consider the simple 3-input, 2-output combinational device whose symbol and

truth table are shown to the left.

The device is in fact a 1-bit

full adder, a building block used

in the constuction of binary adders in subsequent chapters; for now, we

use it simply as an example of combinational functions we might wish to

implement.

The device takes three binary inputs $A$, $B$, and $C_i$ and produces the

two outputs $S$ and $C_o$. Note that we could have split this into two

separate 3-input devices for computing $S$ and $C_o$ respectively;

however, their combination as a single device allows us to exploit some

shared logic for implementation efficiency.

In particular, we will use a single decoder to convert the three input bits

to a more convenient form: a logic $1$ on exactly one of its eight outputs.

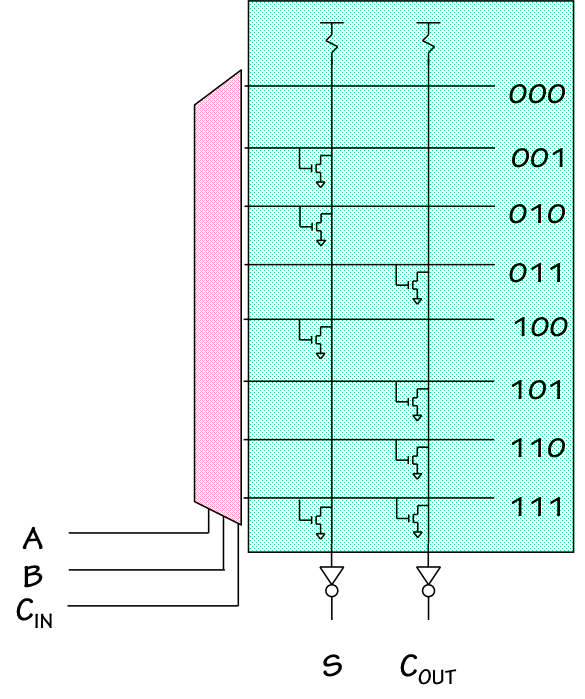

ROM-based Full Adder

ROM-based Full Adder

One approach to the ROM-based full adder is shown to the right.

The three inputs are decoded to drive exactly one of the eight horizontal

lines to $1$; the selected line corresponds to the row of the truth table

selected by the current inputs, or one possible product term in a sum-of-products

expression.

Superimposed over the horizontal decoder outputs are two vertical lines,

each connected to $V_{DD}$ through a resistive pullup. This passive pullup

serves to cause the voltage on each vertical line to have a default value

of $1$.

At each of the intersections between a horizontal decoder output and a vertical

line, there is either no connection or an NFET pulldown.

The presence of a pulldown at an intersection causes a $1$ on the horizontal

line to force the vertical line to $0$, by overpowering the passive resistive

pullup.

Thus each of the vertical lines performs a logical NOR function of the

horizontal lines for which there are pulldowns; an inverter between each

vertical line and the $S$ and $C_o$ outputs causes each output to be a

logical OR of the decoder outputs selected by the presence of pulldowns.

Comparing the diagram with the truth table for the full adder, note that

there are pulldowns at precisely those intersections corresponding to $1$s

in the truth table output columns. Thus the logical function that appears

at each output corresponds to the sum-of-products computation of the functions

represented in the table.

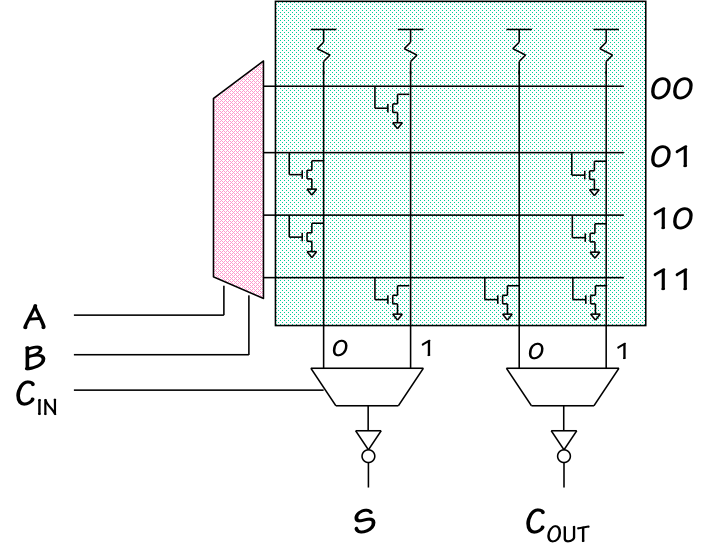

ROM Folding

7.8.3.3. ROM Folding

Although this ROM implementation exploits a second dimension to compute multiple

outputs from a single decoded set of inputs, its vertical dimension still grows

in proportion to $2^k$ where $k$ is the number of inputs.

In general, long lines cause delays; we would prefer to make the ROM array more

nearly square by using a greater number of shorter vertical lines.

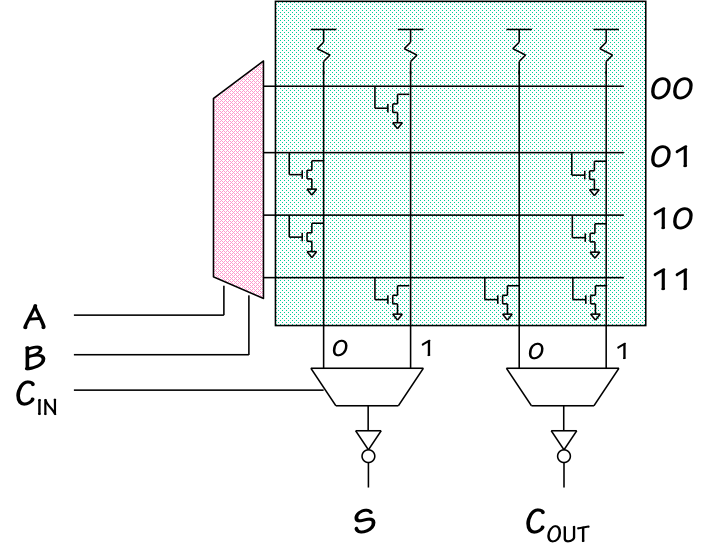

Folded ROM

Folded ROM

Fortunately, this is a fairly straightforward engineering tradeoff.

On the left is shown a revised ROM layout, in which two of the inputs

($A$ and $B$) are decoded onto four horizontal lines rather than the previous eight.

Each output is then computed by two vertical lines, one giving the value for $C_i=0$

and another for $C_i=1$; the $C_i$ input is used in an output multiplexor

for each output to select the proper value.

Commodity/Customization Tradeoffs

7.9. Commodity/Customization Tradeoffs

The design approach taken by ROMs, involving a regular array of

cells sharing the same internal structure, is used in other systematic

logic technologies as well.

These include read-write memories (RAMs) as well as several varieties

of logic arrays.

These approaches exemplify a recurring technology tradeoff between the advantages of

an application-generic, mass-produced commodity implementation and an

application-specific implementation highly optimized around the structure

of a particular solution.

An attractive feature of ROMs and other commoditized approaches is that

nearly all of the structure of a given-size ROM is independent of the

actual function it performs: the customization may be left to a final

parameterization step (adding a metal layer to a chip, or even field

programming in the case of

flash memories or FPGA logic arrays).

Chapter Summary

7.10. Chapter Summary

Having moved from transistors into the logic domain, we face the task

of combining logic elements to synthesize higher-level logical functions.

Techniques explored include:

- While truth tables are an effective tool for the specification

of logic functions, Boolean expressions are often a convenient

alternative. Familiarity with identities and Boolean manipulation

techniques is an important skill for the logic designer.

- Any truth table can easily be translated to a sum-of-products (SOP)

Boolean expression, which can be mechanically converted to a 3-level

gate implementation of the function.

Useful SOP techniques include NAND-NAND and NOR-NOR implementations.

- SOP implementations are not necessarily minimal; function-specific

structure may often be exploited to implement a given function using

fewer CMOS devices.

- Multiplexors are useful building blocks, and can be used to

systematically implement arbitrary functions as lookup tables.

- ROMs generalize this table-lookup implementation approach,

offering a fixed hardware complexity independently of the truth

table details.